It was the early 1900s. Ships left Punjab carrying men with nothing but dreams, turbans, and faith. They were bound for America—the land of opportunity. But many never made it. Instead, they stepped off in Mexico, a country strange and unfamiliar, yet destined to become their home. Some were cheated at the border, some lost their crops to government seizures, and some found love in the arms of Mexican women when laws kept them from reuniting with wives back in India. Their stories are filled with struggle, resilience, and surprising twists of fate. To understand Sikhs in Mexico, we must first listen to these journeys—stories of dreams that didn’t end at the U.S. border, but blossomed in unexpected soil.

Story 1: Farmers in Sonora and Sinaloa (1920s)

In the early 1900s, Sikh farmers from Punjab, such as Gurmit Singh of Jullunder, were lured to northern Mexico by President Obregón’s colonization schemes. They settled in Sonora and Sinaloa, growing crops and hoping to cross later into the United States. But their plans took a bitter turn in the 1930s when government authorities confiscated their harvests, forcing many to abandon farming. Some drifted into U.S. attempts again, but many stayed back, laying roots in Mexico despite hardships. These early settlers cleared arid lands, introducing innovative irrigation techniques from Punjab, only to face xenophobic policies that stripped them of their livelihoods. Yet, their descendants today speak of those fields as sacred ground, where the first Punjabi-Mexican bonds were forged.

Story 2: The Punjabi-Mexican Families

In the early 20th century, U.S. immigration laws prevented Sikh men from bringing their wives from India. On the U.S.–Mexico border, many Punjabis found love and stability with Mexican women, creating Punjabi-Mexican families. These families became cultural bridges—children grew up speaking Spanish, learning Catholic traditions, yet also hearing Punjabi folk tales and tasting homemade rotis. For many, Mexico became home simply because the U.S. never opened its doors.

One poignant example comes from the stories captured in the PBS documentary Roots in the Sand, which chronicles multi-generational Punjabi-Mexican families who settled in southern California after initial stops in Mexico. Take the family of Raghbir Singh, a Punjabi migrant who arrived in Mexicali in the 1910s. Denied entry to the U.S., he married a local woman named Maria Gonzalez. Their children, like daughter Isabella Singh-Gonzalez, grew up navigating dual identities—celebrating Diwali with homemade parathas alongside posadas at Christmas. Isabella later shared in interviews how her father’s turban became a symbol of quiet defiance in a town wary of outsiders, blending Sikh resilience with Mexican warmth. These unions weren’t just survival tactics; they wove a vibrant tapestry of hybrid culture that persists in border communities today. pbs.org

Story 3: Joginder “Jog” Singh’s Border Confrontation (1920s)

Joginder Singh, known as Jog, tried to cross into the U.S. via Mexico during the 1920s. Smugglers demanded he cut his hair and turban to disguise as non-Indian. Jog refused. As a result, he was charged a higher fee but still smuggled across. Many others were not as lucky—those who failed crossings ended up settling in Mexican border towns, blending into local communities rather than returning defeated.

This refusal to abandon faith echoes in more recent accounts. In 2022, U.S. Border Patrol agents in Yuma, Arizona, were accused of confiscating and discarding turbans from at least 64 Sikh asylum seekers crossing from Mexico, treating the sacred headwear as mere contraband. One anonymous Sikh migrant recounted to the ACLU how agents laughed as they tossed his turban into a trash bin, forcing him to cross bareheaded—a profound violation that left him feeling stripped of his identity. Incidents like these highlight the ongoing clash between Sikh devotion and border enforcement, turning what should be a journey of hope into one of humiliation. azluminaria.org. theguardian.com

4.The Silent Crossing at Night of Baldev Singh

In the 1920s, a young Sikh farmer named Baldev Singh left Punjab with dreams of earning money in California’s farms. He reached Mexico after a long sea voyage via Hong Kong and the Pacific coast. With no visa access, his only hope was to cross the border secretly. One moonless night, guided by a local smuggler, he crawled for hours through dry riverbeds near the Rio Grande. He carried only a photo of his family and a packet of parched corn. After hiding in cactus thickets for two days, he finally made it into Texas. Baldev walked for another week until he found seasonal farm work. Years later, he moved to California’s Central Valley, where he grew almonds and quietly became part of the early Sikh farming community. npr.org

5. The Disguise on a Freight Train - Gurbachan Singh

In the 1940s, Gurbachan Singh, a tall man with a turban, realized his appearance drew immediate attention in Mexican towns near the border. To cross, he disguised himself as a Mexican laborer—he cut his beard short, wrapped a bandana around his head, and carried a guitar borrowed from a friend. He boarded a freight train carrying farm workers northward. At a checkpoint, when questioned in broken Spanish, Gurbachan strummed a tune and pretended to be a wandering musician. The guards laughed and waved him through. That daring trick allowed him to reach California, where he later joined other Punjabi-Mexican families and worked in orchards.

6. The Tailor of Puebla - Harbhajan Singh

Harbhajan Singh, who arrived in Mexico in the 1930s, tried multiple times to cross the U.S. border but was turned back each time by patrol officers who noted his distinct turban and non-Spanish accent. With his savings dwindling, he settled in Puebla. Harbhajan had tailoring skills from Punjab, and he opened a small shop stitching clothes for local farmers. Over time, he married María González, a local woman who admired his discipline and kindness. Together they raised three children. Their home blended Sikh customs and Mexican traditions—chapatis on one plate, tortillas on another, with the Guru Granth Sahib kept respectfully in a small corner of the house. sikhglobalvillege.wordpress.com

7. The Farmer Who Grew Chilli and Sugarcane - Kartar Singh

Kartar Singh reached the Mexican border in the 1950s but was caught twice by U.S. authorities and warned against trying again. Defeated, he chose to stay in Veracruz, where the climate reminded him of Punjab. Kartar began working on chili and sugarcane farms. In time, he married Isabella López, the daughter of a farmer. Though Kartar missed Punjab deeply, he found comfort in farming and family. His children grew up speaking Spanish but remembered their father’s Punjabi proverbs and turbaned identity. Today, some of their descendants identify as Punjabi-Mexican, a unique cultural thread linking two distant lands.

Migration Routes and Settlement - Sikhs in Mexico

A modern tale of settlement comes from Arjan Kaur, a Mexican-born Sikh whose life bridges continents. In a 2020 interview, she described growing up in Mexico City, where her Punjabi father ran a small import business after failing to cross into the U.S. in the 1970s. Arjan learned to tie a turban at age 10, blending it with her love for mariachi music, and now advocates for Sikh visibility in Latin America through community workshops. Her story illustrates how Mexico has become not just a transit point, but a place of enduring home for second-generation Sikhs

Sikhism in Mexico Today

Sikhism is not formally recognized as one of Mexico’s mainstream religions, but Sikh communities practice freely.

Gurdwara Sri Guru Singh Sabha in Tecamachalco is the most famous Sikh center in Mexico.

Sikh migrants still use Mexico as a gateway to the U.S. and Canada, though border detentions and deportations are frequent even today. In fiscal year 2023 alone, over 41,000 Indians—including many Sikhs—were encountered at the U.S.-Mexico border, a sharp rise from previous years.

Journeys to the North — Migration Stories (Donkey/Dunki Route)

These recent stories illustrate the modern version of the same old dream—to reach the United States—and the human cost involved. The “donkey route,” or dunki in Punjabi, refers to the perilous overland path through multiple countries, often via Mexico, fraught with smugglers, deserts, and danger. While the provided tales of Sukhpal Singh’s deportation with 104 others, Satpal Singh’s Rs 55 lakh gamble from Ferozepur, and Gurpreet Singh’s tragic death in Central American jungles capture the essence, here are more verified accounts from 2023-2025 that underscore the risks.

Sourav from Ferozepur (February 2025)

A young deportee who spoke candidly upon returning to Punjab, Sourav detailed his grueling odyssey. Leaving India on December 17, 2024, he flew to Malaysia (one week), Mumbai (10 days), Amsterdam, then Panama’s jungles to Tapachula and Mexico City. The final leg to the U.S. border took 3-4 days of trekking. Caught within hours of entry on January 27, 2025, he spent 15-18 days in a detention camp—hands and legs bound, phones confiscated, pleas ignored—before deportation. His family sold land and borrowed to fund Rs 45 lakhs for agents. “We cooperated, but no one listened,” he said, his voice breaking as he appealed for government aid to recover their losses.

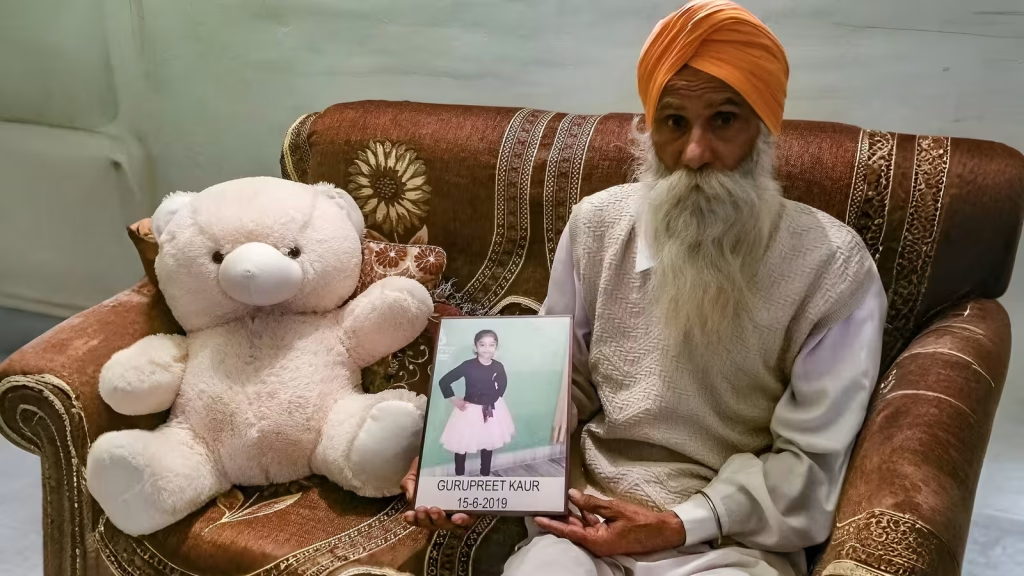

Gurupreet Kaur's Harrowing Crossing (2020, Echoed in Recent Waves)

It was 108 degrees Fahrenheit. The girl, Gurupreet Kaur, and her mother had just crossed illegally into Arizona from Mexico, part of a group of Indian migrants. Gurupreet’s father had gone ahead to the U.S. in 2013, a few months after his daughter was born, and was waiting for them. Mother and daughter left home in early 2019. She died on June 12, 2019, of heatstroke in the desert near Lukeville, Ariz., some 8,000 miles from home.

In a statement issued last year from New York City, where the couple now lives and has applied for asylum, they said they left India because they were “desperate” and wanted “a safer and better life” for their daughter. But they have never explained why they felt unsafe in India and made what they called an “extremely difficult decision” to embark on such a risky journey.

The vast majority of the hundreds of thousands of migrants trying to cross from Mexico into the U.S. each year come from Latin America. But Gurupreet and her parents were among a growing number of Indians risking their lives to cross that border too. npr.org

Anonymous Gujarati-Sikh Family Deportation (February 2025)

50 Punjabis and Haryanvis deported from the U.S.-Mexico border, a Gujarati Sikh family revealed paying Rs 1 crore to agents who routed them via the UK. Apprehended after 10 days of hiding in border scrubland, they described dark detention cells and family separations. One uncle from Amritsar sold 1.5 acres for Rs 42 lakhs to fund his nephew’s attempt—money now lost to “betrayers,” as the youth called the smugglers.

These stories are common enough that entire networks of smugglers, agents, and survival routes have formed—often at the cost of migrants’ lives and family fortunes. Tragically, deaths persist: In 2023-2024, at least a dozen Indian migrants, including Sikhs, perished in Mexico’s migrant caravans from dehydration or violence, though exact figures remain underreported amid the chaos.

Sikhs, Entrepreneurs, and Community Builders in Mexico

While many Sikhs work in small-scale trade and services, a few individuals and families have created notable contributions to Mexican society and to the Sikh community worldwide.

Babaji Singh Khalsa — The Translator

Born in Mexico City (1947) and later converted to Sikhism, Babaji Singh Khalsa devoted decades to translating the Guru Granth Sahib into Spanish—a task that opened Sikh scripture to Spanish-speaking believers across Latin America. His translation work, completed over roughly 30 years, remains a cultural bridge and a testament to deep devotion.

Hari Simran Singh — Entrepreneur & Environmentalist

A Mexican-born Sikh, Hari Simran Singh (also known for work in environmental technologies) led projects aimed at waste solutions and sustainability. His story shows how Sikh values—service (seva) and stewardship—can be expressed through entrepreneurship in Mexico.

Jai Hari Singh (François Valuet) — Yoga and Sikh Lifestyle

Jai Hari Singh, a French-born convert who has lived in Mexico for decades, runs yoga and wellness centers that combine Kundalini Yoga and Sikh-inspired practices. His centers in Mexico City help spread Sikh-influenced spiritual practices, drawing both converts and local practitioners.

Small Businesses & Traders Sikh in Mexico

Many Punjabi-Mexican families run restaurants, grocery shops, tailoring and import-export small businesses. Restaurants with Punjabi touches, textile trade, and transport-related enterprises are common.

These small businesses are often family-run and act as cultural anchors for Sikh communities in Mexican cities. For instance, in Mexicali, descendants of 1920s migrants like those profiled by anthropologist Karen Leonard operate tiendas blending masala chai with café de olla, preserving Punjabi recipes amid Mexican flair. saada.org

-

Sikhs in Kerala

Sikhs in Kerala: A Unique Chapter in Sikh Migration Welcome to Global Sikhi Wiki, your comprehensive resource for exploring Sikh history, culture, and communities. Today, we delve into the vibrant story

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Greenland

Sikhs in Greenland: A Glimpse into the Frozen Diaspora Welcome to Global Sikhi Wiki, your comprehensive resource for exploring Sikh history, culture, and global communities. Today, we delve into the

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Delhi

Sikhs in Delhi- Overview Delhi occupies a foundational position in Sikh history, not as a peripheral settlement but as a sacred and political site shaped during the Guru period and

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Shamshabad

Sikhs in Shamshabad: How a Tribal Village in Telangana, India Turned to Sikhism Welcome to Global Sikhi Wiki, your comprehensive resource for exploring Sikh history, culture, and communities. Today, we delve

Published by Pritam -

Canadian Sikh lawyer Oath

Prabhjot Singh — Canadian Sikh Lawyer Who Challenged the Mandatory Oath Who Is Prabhjot Singh? Prabhjot Singh (full name Prabhjot Singh Wirring) is a Canadian lawyer of Sikh heritage. He

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Ukraine

UNITED SIKHS has been a prominent humanitarian responder in Ukraine since the 2022 invasion, providing immediate relief like food, medical aid, and shelter near borders and within war-torn cities like Kyiv and

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Austria

Sikhs in Austria: A Flourishing Community in the Heart of Europe Welcome to Global Sikhi Wiki, your comprehensive resource for exploring Sikh history, culture, and global communities. Today, we delve

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Finland

Sikhs in Finland: Migration, Turban Rights, Gurdwaras Welcome to Global Sikhi Wiki, your comprehensive resource for exploring Sikh history, culture, and global communities. Today, we delve into the vibrant story

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Israel

Sikhs in Israel: A Hidden Chapter of Global Sikh History Welcome to Global Sikhi Wiki, your comprehensive resource for exploring Sikh history, culture, and global communities. Today, we delve into

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Chile

Sikhs in Chile: A Small but Vibrant Community in South America Welcome to Global Sikhi Wiki, your comprehensive resource for exploring Sikh history, culture, and global communities. Today, we delve

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Bermuda

Sikhs in Bermuda: A British Overseas Territory Welcome to Global Sikhi Wiki, your comprehensive resource for exploring Sikh history, culture, and global communities. Today, we delve into the vibrant story

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Belize

Sikhs in Belize — a small but significant thread in the Caribbean Welcome to Global Sikhi Wiki, your comprehensive resource for exploring Sikh history, culture, and global communities. Today, we

Published by Pritam -

Why a New York Street Honors a Sikh Guru

Why a New York Street Honors a Sikh Guru-Guru Teg Bahadur Ji Marg Way A Historic Honor in New York Welcome to Global Sikhi Wiki, your comprehensive resource for exploring

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Malaysia – From Struggle to Strength

Sikhs in Malaysia: A Tapestry of Courage, Faith, and Unyielding Spirit Welcome to Global Sikhi Wiki, your comprehensive resource for exploring Sikh history, culture, and global communities. Today, we delve

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in France

Sikhs in Malaysia: A Tapestry of Courage, Faith, and Unyielding Spirit Welcome to Global Sikhi Wiki, your comprehensive resource for exploring Sikh history, culture, and global communities. Today, we delve

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Fiji

Sikhs in Fiji: A Journey of Resilience and Contribution in Modern Oceania Welcome to Global Sikhi Wiki! In this blog post, we explore the vibrant history and enduring legacy of

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Germany

Sikhs in Germany – Building Faith and Community in Modern Europe Germany, the land of poets, philosophers, and thinkers, is home to one of the lesser-known yet deeply rooted Sikh

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Japan

Sikhs in Japan : Small Community, Big Stories Among all the countries I’ve studied, Japan is perhaps the first where I found no illegal Sikh immigration network — just a

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Argentina

Sikhs in Argentina: Bibiana Jasbe Singh Kaur Born in Argentina, Bibiana straddles two identities. Though her Sikh ancestors forbade beef, she acknowledges that at social events and in local culture,

Published by Pritam -

The Heartbreaking Journey of Harjit Kaur

The Heartbreaking Journey of Harjit Kaur In the dusty villages of Punjab, where the mustard fields sway like whispers of forgotten dreams under the relentless Indian sun, Harjit Kaur was

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Mexico

Sikhs in Mexico: Forgotten Journeys and Resilient Roots By [ Global Sikhi Wiki Team] | Published on GlobalSikhiWiki.com | September 23, 2025 IST It was the early 1900s. Ships left

Published by Pritam -

The Bitter Exodus of Sikhs from Afghanistan

The Bitter Exodus of Sikhs from Afghanistan Picture this: The sun rises over Kabul's ancient bazaars in the 1970s, where the air hums with the chatter of turbaned Sikh traders

Published by Pritam -

Decline of Sikhs in China

The Decline of Sikhs in China: A Multifaceted Historical Narrative The history of Sikhs in China is a poignant, often overlooked chapter in the global Sikh diaspora, marked by a

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in Afghanistan

The Untold Story of Sikhs in Afghanistan - From Prosperity to Perseverance Imagine the bustling streets of Kabul in the 1970s—a vibrant mosaic of cultures where turbaned Sikh merchants haggled

Published by Pritam -

Sikhs in China

Sikhs in China: A Hidden Chapter of Sikh Heritage Hello, readers! Welcome to another intriguing exploration of Sikh heritage on GlobalSikhiWiki.com. Imagine a turbaned Sikh policeman patrolling the bustling streets

Published by Pritam

-

Sikhs in Kerala

Sikhs in Kerala

-

Sikhs in Greenland

Sikhs in Greenland

-

Sikhs in Delhi

Sikhs in Delhi

-

Sikhs in Shamshabad

Sikhs in Shamshabad

-

Canadian Sikh lawyer Oath

Canadian Sikh lawyer Oath

-

Sikhs in Ukraine

Sikhs in Ukraine

-

Sikhs in Austria

Sikhs in Austria

-

Sikhs in Finland

Sikhs in Finland

-

Sikhs in Israel

Sikhs in Israel

-

Sikhs in Chile

Sikhs in Chile

-

Sikhs in Bermuda

Sikhs in Bermuda

-

Sikhs in Belize

Sikhs in Belize

-

Why a New York Street Honors a Sikh Guru

Why a New York Street Honors a Sikh Guru

-

Sikhs in Malaysia – From Struggle to Strength

Sikhs in Malaysia – From Struggle to Strength

-

Sikhs in France

Sikhs in France

-

Sikhs in Fiji

Sikhs in Fiji

-

Sikhs in Germany

Sikhs in Germany

-

Sikhs in Japan

Sikhs in Japan

-

Sikhs in Argentina

Sikhs in Argentina

-

The Heartbreaking Journey of Harjit Kaur

The Heartbreaking Journey of Harjit Kaur

-

Sikhs in Mexico

Sikhs in Mexico

-

The Bitter Exodus of Sikhs from Afghanistan

The Bitter Exodus of Sikhs from Afghanistan

-

Decline of Sikhs in China

Decline of Sikhs in China

-

Sikhs in Afghanistan

Sikhs in Afghanistan

-

Sikhs in China

Sikhs in China