About Kenya: A Land of Diversity and Opportunity

Kenya,5016 Km from India, located in East Africa, is renowned for its stunning landscapes, vibrant culture, and rich wildlife.

Capital and Population: Nairobi is the capital and largest city, with a population of over 55 million.

Language: English and Swahili are the official languages.

Economy: Kenya has a mixed economy driven by agriculture, services, and tourism.

Wildlife: The country is famous worldwide for its national parks and safari experiences.

Some of the Famous Sikhs of Kenya

Sikhs Migration to Kenya

Sikh migration to Kenya began in the late 19th century during British colonial rule, primarily as part of the British East Africa Protectorate established in 1895. The British recruited Sikhs from Punjab, India, for their skills and military background to support colonial infrastructure projects and administration. Below is a detailed overview of how and when Sikhs migrated to Kenya, based on historical context and available information: The Man-Eaters of Tsavo

When Sikhs Migrated to Kenya-

1.Late 1890s :

Initial Migration for Railway Construction

– The primary catalyst for Sikh migration was the construction of the Uganda Railway (1896–1901), which connected Mombasa to Kisumu and later extended to Kampala, Uganda. SikhNet

The British brought approximately 32,000 indentured laborers from India, including many Sikhs, to work on this ambitious project. Sikhs were valued for their skills as carpenters, blacksmiths, masons, and engineers, with many adapting to specialized roles like fitters and boilermakers.

– Recruitment was centered in Lahore, Punjab, where Sikhs from surrounding villages were transported via special trains to Karachi and then shipped to Mombasa on British India Steam Navigation Company vessels. WikiPedia

– The railway construction was dangerous, with around 2,500 laborers dying due to harsh conditions, diseases like malaria, and attacks by wildlife, including the infamous Tsavo man-eating lions, which reportedly targeted Sikh workers. Despite these challenges, many Sikhs completed their contracts and chose to stay in Kenya, bringing their families from India. SikhiWiki

2. 1900s–1930s: Voluntary Migration and Settlement

– After the railway’s completion in 1901, many Sikhs settled in Kenya, particularly in urban centers like Nairobi and Mombasa. They were joined by voluntary migrants, primarily Punjabis, including Sikhs, who sought economic opportunities in trade, commerce, and skilled professions.

– Sikhs established businesses, schools, and gurdwaras (Sikh temples), contributing to the economic and cultural fabric of the region. Notable early gurdwaras included the Makindu Sahib Gurdwara (1902) and the Railways Landhis Gurdwara in Nairobi (1902), which became central to Sikh community life.

– By the 1930s, Sikhs had become prominent in mechanics, construction, and farming, particularly around Lake Victoria, leveraging their skills and work ethic to build prosperous lives. INDIA AND INDIAN DIASPORA IN EAST AFRICA -PDF

3. 1940s–1960s: Professional Migration and Growth

– Post-World War II, Sikh migration included professionals such as teachers, doctors, and administrators, further strengthening their presence in Kenya’s urban areas.

– The Sikh community grew in influence, dominating trade and commerce, with 80–90% of commercial trade in Kenya and Uganda controlled by Indian communities, including Sikhs, by the 1940s.

– However, colonial policies restricted Asians, including Sikhs, from settling in the cooler Highlands, reserved for Europeans, leading to tensions that persisted for decades.

4.Post-Independence (1963 Onward):

Challenges and Continued Presence

– After Kenya’s independence in 1963, the “Africanization” policies under Jomo Kenyatta’s government required non-citizens to acquire Kenyan citizenship or face discrimination. Many Sikhs, holding British passports, faced challenges, and some migrated to the UK or elsewhere.

– Despite this, the Sikh community remained resilient, maintaining their cultural identity through gurdwaras and institutions like the Sikh Union Club, established in the 1920s.

– The expulsion of Asians from Uganda in 1972 under Idi Amin indirectly affected Kenyan Sikhs, as some Ugandan Sikhs relocated to Kenya or other countries, reinforcing the transnational nature of the Sikh diaspora. UKCPA

How Sikhs Migrated to Kenya-

Sikh migration to Kenya was facilitated by British colonial networks and driven by economic and professional opportunities:

1.Colonial Recruitment

– The British leveraged their control over Punjab, where Sikhs were a significant part of the British Indian Army and civil service, to recruit skilled workers for Kenya. Sikhs were seen as reliable and disciplined, making them ideal for roles in railway construction, policing, and administration.

– Sikhs arrived as indentured laborers, soldiers, and police officers. For example, in 1895, Sikhs were brought to Mombasa to police the Uganda Railway and caravan routes, and their military presence intensified during events like the Kabaka’s uprising in Uganda (1898).

2.Travel and Settlement

– Most Sikhs traveled by sea, enduring long journeys on steamships or dhows across the Indian Ocean from ports like Karachi or Bombay to Mombasa. These journeys could take months and were arduous, with families often joining later.

– Upon arrival, Sikhs settled in urban centers like Nairobi, which became the capital in 1905, where they were legally permitted to reside, unlike Black Africans. They established close-knit communities, building gurdwaras that served as places of worship, community centers, and rest houses.

3.Economic and Social Integration

– Sikhs quickly adapted to Kenya’s economic landscape, excelling in skilled trades, entrepreneurship, and agriculture. Notable figures like A.M. Jeevanjee, who supplied labor for the Uganda Railway and founded Kenya’s first newspaper (The Standard), exemplified Sikh enterprise.

– The Sikh community’s distinct identity, marked by their turbans and beards, earned them the nickname “Kalasingha” (derived from a pioneer Sikh named Kala Singh in the 1890s), a term of respect used by local Africans.

– Sikhs contributed significantly to Kenya’s development, from building infrastructure to participating in sports (e.g., the Sikh Union Club) and politics (e.g., Makhan Singh, a prominent freedom fighter).

Cultural and Historical Impact

Gurdwaras and Community

Sikhs established numerous gurdwaras, such as Makindu Sahib, which became a landmark for its open-door policy, offering food and shelter to all. These institutions preserved Sikh identity and Punjabiyat (Punjabi culture) in Kenya. Leave only Footprints

-Challenges:

Sikhs faced dangers during railway construction, including wildlife attacks and diseases, and later navigated colonial racism and post-independence discrimination. Despite these, their resilience and adaptability made them a respected community, often called “simbas” (lions) by locals.

-Modern Presence:

Today, the Sikh population in Kenya is estimated at 7,000–21,000, concentrated in urban areas like Nairobi and Nakuru. They remain influential in business, medicine, politics, and sports, with a unique Kenyan-Punjabi dialect influenced by Swahili.

Conclusion

Sikh migration to Kenya began in the 1890s with the British recruitment of skilled laborers for the Uganda Railway, followed by voluntary migrations for trade and professional opportunities. Despite challenges like colonial restrictions, wildlife threats, and post-independence policies, Sikhs established a vibrant, respected community in Kenya, contributing significantly to its economic and cultural landscape. Their legacy endures through gurdwaras, businesses, and a distinct identity as the “Kalasingha” tribe.

How Sikhs Dominated Hockey in Kenya

Sikhs have played a pivotal role in shaping field hockey in Kenya, establishing a legacy of dominance from the early 20th century through the 1980s. Their influence stemmed from a combination of cultural affinity for sports, institutional support through the Sikh Union Club, and strategic roles in coaching and administration. Here’s a detailed look at how Sikhs dominated Kenyan hockey.

1. Early Introduction and Cultural Roots

Sikhs introduced hockey to Kenya around 1900, alongside Goan communities, with the sport gaining traction among Punjabis due to their familiarity with stick-based games.

By the 1920s, Sikhs were actively playing hockey, as evidenced by records from the Kenya Asian Sports Association, founded in 1912.

The Sikh Union Club, established in Nairobi in the mid-1920s, became the epicenter of Sikh hockey, fostering young talent and dominating domestic competitions.

2. Sikh Union Club’s Central Role:

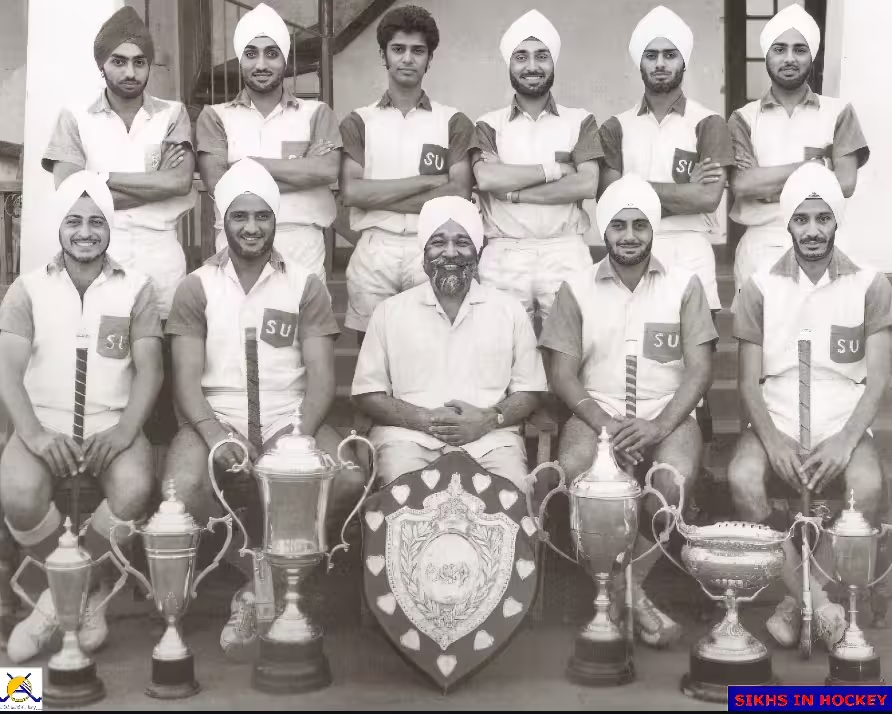

The Sikh Union Club in Nairobi was the backbone of Kenyan hockey, producing a majority of national team players and winning numerous domestic trophies in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.

The club’s success was driven by a culture of mentorship, where veteran players like Mahan Singh and Hardial Singh coached younger generations, ensuring a steady pipeline of talent. SikhUnionClub

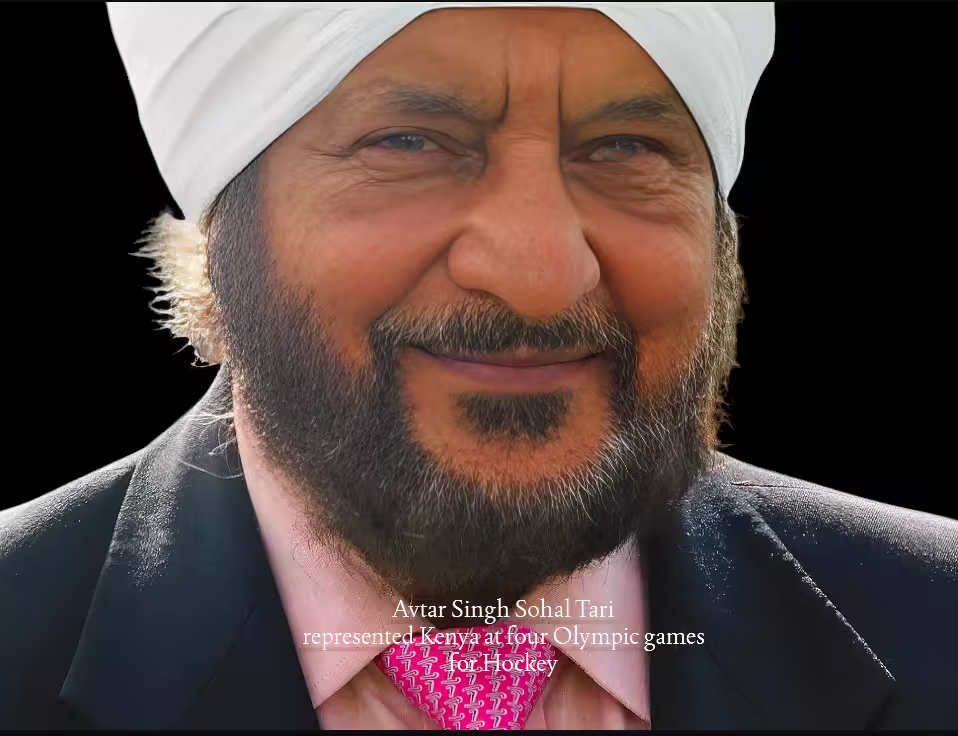

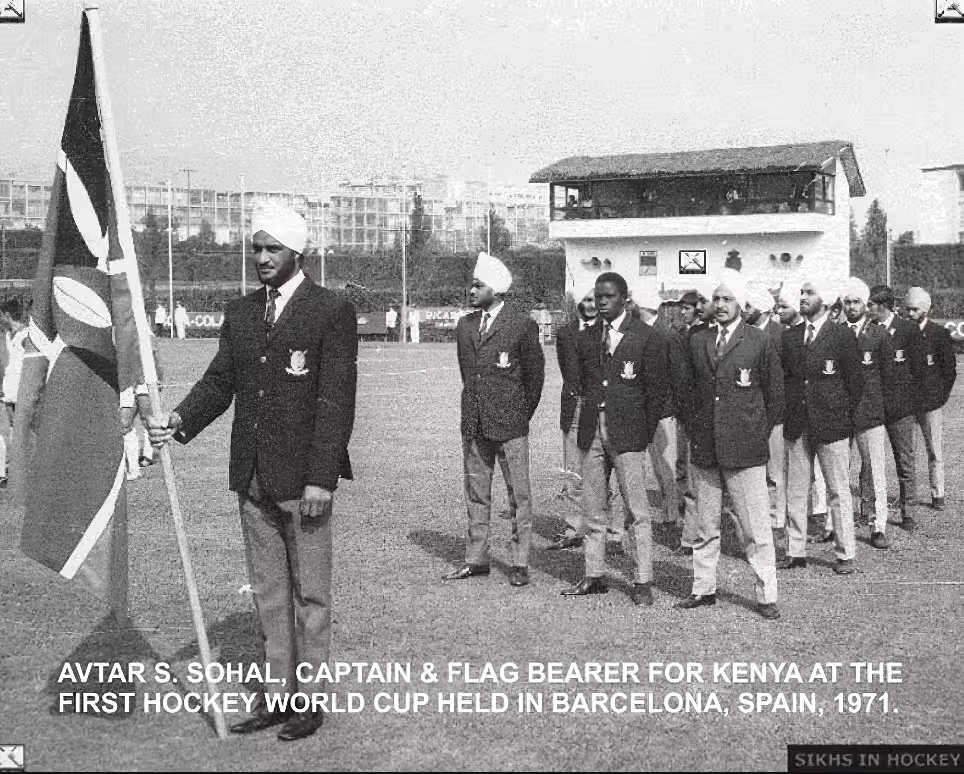

Sikh Union’s defensive prowess, epitomized by players like Avtar Singh Sohal, earned them a reputation for “impenetrable” play, with their motto likened to “none shall pass.”

Other Sikh Union clubs in Mombasa, Nakuru, Eldoret, and Nyeri also contributed to hockey’s growth across Kenya. SIKHS IN HOCKEY

3. Dominance in National and International Hockey Teams

Sikhs formed the bulk of Kenya’s national hockey teams, particularly during Olympic participations. For example, they accounted for eight players in 1956, nine in 1960, and six in 1964.

In the 1972 Munich Olympics, 13 of the Kenyan team’s players were Sikhs, showcasing their overwhelming presence.

Kenya’s historic fourth-place finish at the 1971 World Cup in Barcelona was heavily driven by Sikh players from Sikh Union, including stars like Avtar Singh Sohal and Surjit Singh Rihal. Daily Nation

4. Control of Hockey Administration

Sikhs held influential positions in the Kenya Hockey Union (KHU), formed in 1949, with figures like Mahan Singh serving as secretary and later president.

Coaches like Hardial Singh (1960–1966) and Hardev Singh shaped national teams, though their dominance led to accusations of nepotism and Nairobi-centric bias, particularly from Goan communities. Issuu

This administrative control ensured Sikh players were consistently selected, reinforcing their dominance but also fueling rivalries with Goans.

5. Rivalry with Goans

The Sikh-Goan rivalry defined Kenyan hockey, described as unparalleled globally for its intensity between two communities vying for club, national, and Olympic supremacy.

Sikh Union’s defensive style clashed with the Goans’ flair, led by players like Alu Mendonca. This rivalry elevated the sport’s quality, with matches drawing passionate crowds akin to major football derbies. FIH.CH

5. Post-Independence Challenges and Legacy

After Kenya’s independence in 1963, “Africanization” policies and emigration to the UK and Canada reduced Sikh numbers, but their hockey legacy persisted through clubs like Sikh Union.

By the 1980s, Sikh Union Nairobi continued to produce Olympians and World Cup players, with Narinder Singh Chana noting the club’s contribution of 26 Olympians and 13 World Cup participants.

The club’s decline in the 2000s, culminating in relegation in 2019, marked a shift, but their sports academy signals efforts to revive their dominance.

Conclusion - Kenyan Hockey

Sikhs dominated Kenyan hockey through the Sikh Union Club’s institutional strength, their significant representation in national teams, and influential roles in coaching and administration. Their rivalry with Goans pushed the sport to new heights, producing a golden era marked by Olympic and World Cup appearances. Players like Avtar Singh Sohal, Surjeet Singh Deol, and Amarjeet Singh Marwa stand out as legends, with Sikh Union’s legacy enduring despite modern challenges. The club’s contribution of 26 Olympians and 13 World Cup players underscores the Sikh community’s profound impact on Kenyan hockey. DailyNation

Political Achievements of Sikhs in Kenya

The political entry of Sikhs in Kenya and their achievements reflect their significant contributions to the country’s socio-political landscape, despite their relatively small population (estimated at 7,000–21,000). Sikhs, who began migrating to Kenya in the late 19th century as part of British colonial efforts, transitioned from laborers, soldiers, and traders to influential figures in politics, trade unions, and community leadership. Their political involvement was shaped by their struggle against colonial discrimination, advocacy for workers’ rights, and post-independence contributions to Kenyan nation-building. Scroll

Political Entry of Sikhs in Kenya

Colonial Era (1890s–1963):

Initial Roles:

Sikh migration to Kenya began in the 1890s with the British recruitment of Punjabis for the Uganda Railway construction. Sikhs, valued for their skills and discipline, also served as soldiers and police officers, giving them early exposure to administrative structures.

Formation of Associations:

By the 1920s, Sikhs organized through community institutions like the Sikh Union Club and gurdwaras, which became platforms for social and political mobilization. The East African Indian National Congress (EAINC), formed in 1914, included Sikhs in advocating for Indian rights against colonial policies that favored European settlers.

Trade Unionism and Resistance:

Sikhs played a pivotal role in early labor movements. The most notable figure, Makhan Singh, emerged in the 1930s as a trade unionist, challenging colonial labor exploitation and racial discrimination. His work marked a shift from behind-the-scenes cooperation to open resistance, aligning with Sikh principles of justice and equality.

Struggle Against Discrimination:

Sikhs, along with other Indian communities, faced restrictions on land ownership in the Kenyan Highlands and political representation. Their advocacy through organizations like the EAINC pressured the British for reforms, including representation in the Legislative Council (LegCo).

Pre-Independence Activism (1940s–1960s):

Makhan Singh’s Leadership:

Makhan Singh, a Sikh trade unionist, founded the Labour Trade Union of Kenya in 1935 and later the East African Trade Union Congress. His activism, including organizing strikes, challenged colonial labor policies and united African and Indian workers, laying the groundwork for broader political movements.

Political Representation:

Sikhs began gaining formal political roles in the colonial Legislative Council. Figures like Chanan Singh and Fitzval de Souza (though Goan, collaborated with Sikhs) represented Indian interests, advocating for equal rights and opposing racial segregation.

Freedom Movement:

Sikhs supported Kenya’s independence struggle, with Makhan Singh working alongside African leaders like Jomo Kenyatta. His arrest and detention from 1950 to 1961 for trade union activities underscored the Sikh community’s commitment to anti-colonial resistance.

Post-Independence Era (1963–Present):

Integration and Challenges:

After Kenya’s independence in 1963, “Africanization” policies required non-citizens to take Kenyan citizenship or face discrimination. Many Sikhs, holding British passports, faced challenges, but those who stayed contributed to politics through local governance and community leadership.

Continued Influence:

Sikhs maintained influence through business, education, and sports, indirectly supporting political engagement. Gurdwaras and institutions like the Sikh Union Club remained hubs for community advocacy, though direct political representation was limited compared to the colonial era.

Modern Contributions:

Sikhs have served in local government roles, such as city councils, and contributed to Kenya’s multicultural identity. Their political engagement has often focused on community welfare, education, and economic development, aligning with Sikh principles of seva (selfless service).

How Sikhs Established Sikh Gurudwaras in Kenya

The Sikh community’s establishment of gurdwaras in Kenya, their encounters with racial challenges, the history of notable gurdwaras, and the current number of gurdwaras reflect their resilience and cultural contributions in a colonial and post-colonial context.

Sikhs began migrating to Kenya in the 1890s as part of British colonial efforts to build the Uganda Railway, bringing skilled workers like carpenters, blacksmiths, and masons from Punjab. Their ability to establish gurdwaras was driven by their strong community organization, economic success, and cultural commitment to Sikhism. Here’s how they achieved this:

1. Community Organization and Resources

Early gurdwaras were established by pooling resources from Sikh laborers, traders, and professionals who settled in Kenya after completing railway contracts.

The Sikh Union Club, founded in the 1920s in Nairobi, and other community organizations like the Singh Sabha provided institutional support for building and maintaining gurdwaras. These groups facilitated fundraising and land acquisition for religious sites.

Gurdwaras were often built in urban centers like Nairobi and Mombasa, where Sikhs had established economic footholds through trade, construction, and administration, providing the financial stability needed for such projects.

2. Colonial Support and Land Access

The British colonial administration permitted Asians, including Sikhs, to settle in urban areas like Nairobi, unlike Black Africans, who faced restrictions. This allowed Sikhs to secure land for gurdwaras in cities, often near railway stations or commercial hubs where they worked.

For example, the Sikh Temple Landia in Nairobi, established in 1902, was built near the railway, reflecting the community’s early presence and influence in the railway project.

Sikhs’ roles as skilled workers and police officers gave them a degree of favor with the British, facilitating permissions to build religious sites, though they still faced racial restrictions in other areas. WORLD GURDWARA

3. Cultural and Religious Commitment

Gurdwaras were central to maintaining Sikh identity (Punjabiyat) in a foreign land. The Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh scripture, was installed in gurdwaras, transforming even simple structures into sacred spaces.

Early gurdwaras, like Makindu Sahib (1902), were built as dharamsalas (religious resthouses) to serve Sikh laborers and travelers, evolving into full-fledged gurdwaras as communities grew. TheGurdwarasPluralismProject

The Sikh principle of seva (selfless service) drove volunteers to construct and maintain gurdwaras, with langar (free community kitchen) serving all, regardless of race or religion, reinforcing their social role.

4. Adaptability and Initiative

Sikhs adapted to local conditions, building gurdwaras with available materials and labor. For instance, Makindu Sahib’s early structure was simple, serving as a resthouse for railway workers before becoming a major pilgrimage site.

Their success in diverse fields—construction, trade, farming, and healthcare—provided the economic foundation to fund gurdwaras. By the 1930s, Sikhs controlled significant portions of Kenya’s commercial trade, enabling investments in community infrastructure. HistoricalGurudwaras

Racial Problems Faced by Sikhs in Kenya

1.Colonial Era (1890s–1963):

Racial Hierarchy:

The British colonial system placed Europeans at the top, followed by Asians (including Sikhs), and Black Africans at the bottom. Sikhs faced discrimination in land ownership, as the Kenyan Highlands were reserved for European settlers, restricting Sikhs to urban areas. DiscoverSikhism

Labor Exploitation:

During the Uganda Railway construction, Sikh laborers endured harsh conditions, including low wages, dangerous work environments, and attacks by wildlife like the Tsavo man-eating lions, which reportedly targeted Sikhs. Approximately 2,500 laborers, many Sikh, died due to disease, accidents, or lion attacks.

Limited Political Rights:

Asians, including Sikhs, had restricted political representation. The East African Indian National Congress (EAINC), in which Sikhs participated, fought for voting rights and representation in the Legislative Council, but progress was slow until the 1920s.

Social Segregation:

Sikhs faced social exclusion from European communities, who viewed them as inferior despite their contributions. Kalasinhas .This led to tensions, though Sikhs were respected by Africans as “Kalasinghas” for their skills and work ethic. Kalasinghas

Post-Independence Era (1963–Present)

Africanization Policies:

After Kenya’s independence in 1963, Jomo Kenyatta’s government implemented policies requiring non-citizens to take Kenyan citizenship or face discrimination in employment and business. Many Sikhs, holding British passports, were marginalized, prompting some to emigrate to the UK or Canada

Economic Resentments:

Sikhs’ dominance in trade and commerce (controlling 80–90% of commercial trade in Kenya and Uganda by the 1940s) led to tensions with African communities, who perceived Asians as economic competitors. This fueled anti-Asian sentiment in the 1960s and 1970s.

Uganda’s Impact:

The 1972 expulsion of Asians from Uganda under Idi Amin heightened fears among Kenyan Sikhs, though Kenya did not implement similar measures. Some Ugandan Sikhs relocated to Kenya, reinforcing the community’s resilience but also highlighting their vulnerability as a minority.

Cultural Misunderstandings:

Sikhs’ distinct identity—marked by turbans, beards, and the kirpan—sometimes led to misunderstandings or prejudice, though their langar and community service helped build bridges with other groups.

Sikh Response to Racial Challenges:

Sikhs countered discrimination through community solidarity, with gurdwaras serving as safe spaces for cultural and political organization. Figures like Makhan Singh used trade unions to unite African and Indian workers against colonial oppression.

The Sikh Union Club and gurdwaras provided platforms for advocacy, education, and sports, fostering integration while preserving Sikh identity.

Despite challenges, Sikhs earned respect for their contributions, with Africans calling them “simbas” (lions) for their courage and enterprise. Sikhsin Kenya