Sikhs in Finland: Migration, Turban Rights, Gurdwaras

Welcome to Global Sikhi Wiki, your comprehensive resource for exploring Sikh history, culture, and global communities. Today, we delve into the vibrant story of Sikhs in Finland.

Finland—known for its breathtaking lakes, advanced education system, and the surreal Midnight Sun (where the sun stays visible for up to four months in Lapland)—is one of Europe’s northernmost countries. It borders Sweden, Norway, Russia, and the Baltic Sea, and lies nearly 5,000 km from India. With a population of about 5.6 million, Finland today hosts a small but vibrant Indian diaspora, including the Sikh community, estimated at 600–700 Sikhs, mostly settled in Helsinki, Espoo, and Vantaa.

This blog explores the lesser-known history of Sikhs in Finland—from early arrival stories and migration patterns to legal battles for the right to wear the turban, the establishment of Gurdwara Sahib Finland, and evolving cultural practices in this Nordic nation.

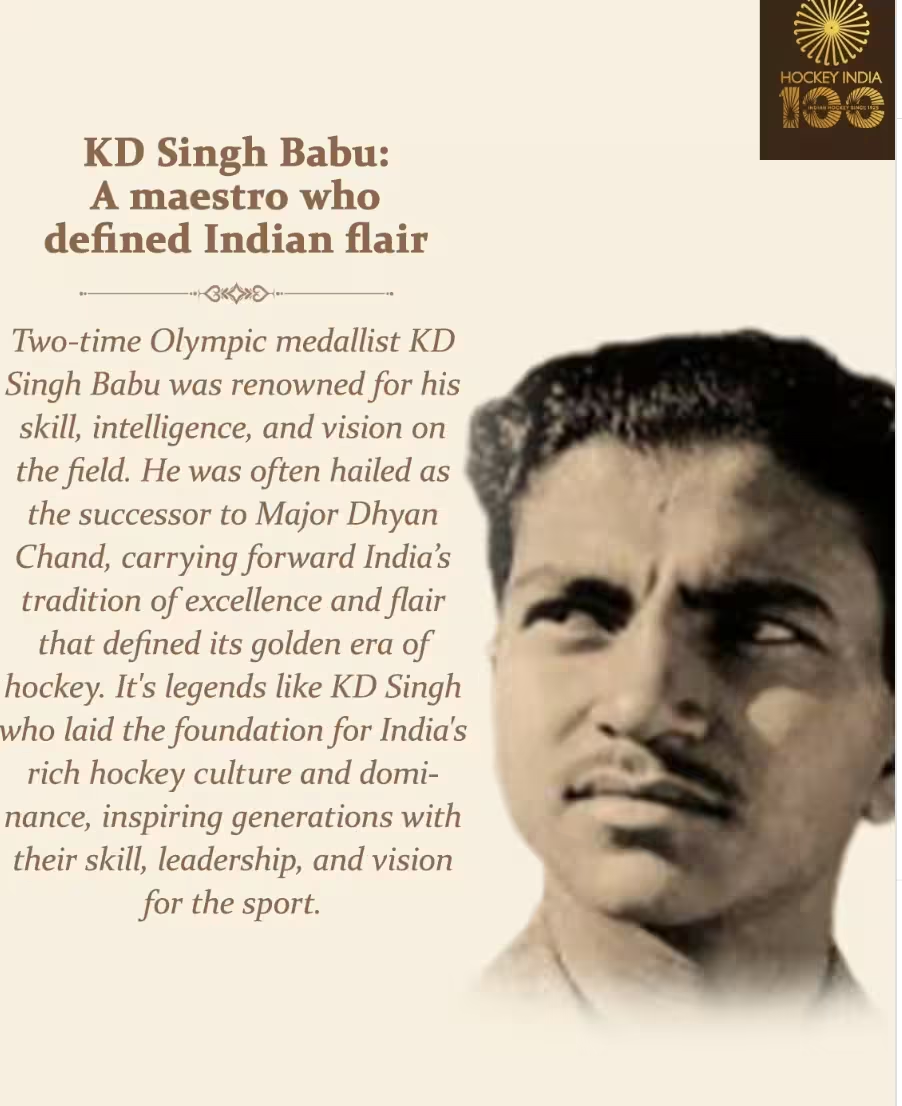

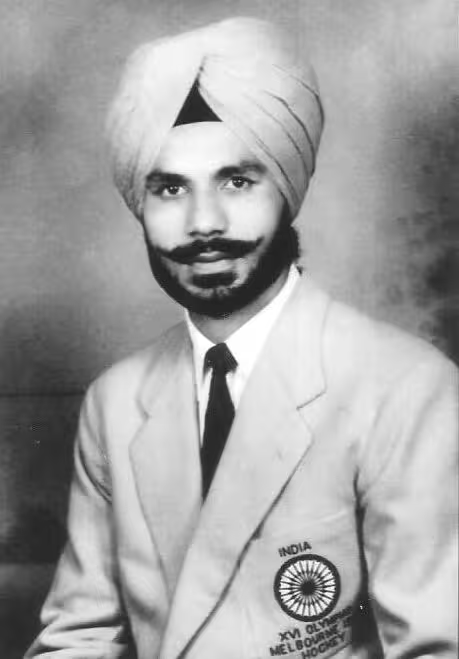

Sikh Hockey Team 1952 in Helsinki

A documented early contact between Sikhs and Finland occurred in 1952, when several turbaned Sikh players were part of the Indian men’s field hockey team that traveled to Helsinki for the Summer Olympics, where India won the gold medal. This was the first known occasion when a recognizable group of Sikhs visited Finland as part of an official, high-profile international event.

In 1970, an Indian hockey delegation again visited Helsinki, this time as part of a sports and cultural exchange program, rather than for a major tournament. Unlike the Olympic visit, the 1970 tour did not lead to long-term settlement, and no Sikh players remained in the country afterward.

The first permanent Sikh migration to Finland began later, during the late 1970s and early 1980s, when individuals arrived for work and study, laying the foundations of today’s Sikh community in Finland.

Who Was the First Sikh in Finland?

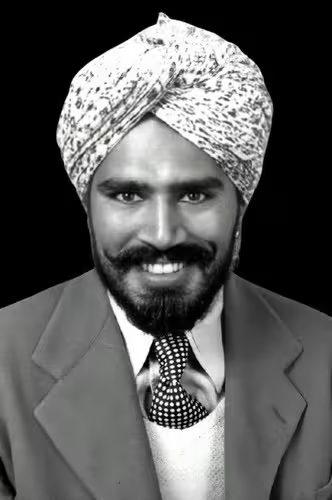

Community histories and Finnish news archives consistently recognize Sudarshan Singh Gill (also known as Gill Sukhdarshan Singh) as one of the first Sikhs in Finland and a pioneering figure in the history of Sikh migration to Finland. His contributions significantly strengthened Sikh identity in the Nordic region, especially through his landmark legal victory affirming the right to wear a Sikh turban in Finland.

Arrival in Finland (1985) – Early Sikh Migration

Gill arrived in Finland in 1985, during the early wave of Sikh migration to Europe. At the time, the Sikh presence in Finland was minimal—limited mostly to earlier short-term contacts, such as the Sikh players in India’s 1952 Helsinki Olympic hockey team. His arrival marks an important milestone in the timeline of Sikhs in Finland.

Pioneering Role in Finland’s Sikh Community

As an early community member, Gill became a foundational figure in establishing Sikh culture, Sikh visibility, and multicultural understanding in Finland. His work helped shape the early development of the Sikh community in a country where South Asian migration was still emerging.

The Turban Legal Case – Religious Freedom in Finland

While working as a bus driver for Veolia Transport Vantaa, Gill was instructed to remove his turban to comply with company uniform rules. Challenging this order, he initiated a year-long legal battle centered on religious freedom, minority rights, and workplace equality in Finland. The case received national attention and contributed to discussions on immigrant rights and Sikh identity in Europe.

Victory and Legacy (2014)

In February 2014, Gill won the case when an agreement between the Transport Workers’ Union (AKT) and the Employers’ Association (ALT) established the right for Sikh employees to wear a turban—either personal or company-issued—while on duty. This ruling has since been regarded as a landmark decision in Sikh rights in Finland.

Community Contributions

Gill later founded the Indian Cultural Club Finland Ry, a community organization promoting multiculturalism and intercultural dialogue.

His son, Sukhnavdeep Singh Gill, continues the advocacy by promoting the right for Sikhs to wear turbans during Finnish military service, noting that countries like Norway and Sweden already permit this.

In most workplaces—from tech companies (like Nokia) and universities to government offices and retail—Sikhs wear turbans without issue. Finland is a secular but tolerant society.

Why Sikh Migration to Finland Started Late

Sikh migration to Finland began relatively late compared to other European countries—particularly other Nordic nations like Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, where significant Punjabi-Sikh communities formed in the 1960s and 1970s. The first permanent Sikh settlers arrived in Finland around 1980, with numbers remaining small (around 600–700 today) and concentrated in the Helsinki area. This delay can be attributed to a combination of Finland’s national immigration dynamics, economic conditions, and the specific migration patterns of Sikhs from Punjab.

Finland was historically a major source of emigrants rather than a destination for immigrants, which limited inflows from anywhere, including South Asia, until the late 20th century:

- Net Emigration Until the 1980s: Post-World War II, Finland experienced massive outward migration, with over 730,000 Finns (about 15% of the population) leaving for better opportunities, primarily in Sweden, due to economic hardships, high unemployment, and industrial needs abroad. Between 1969 and 1979 alone, nearly 400,000 Finns emigrated to Sweden. This “emigration era” meant Finland had little appeal as a settlement destination and few established immigrant networks to draw newcomers.

- Economic Turnaround and Policy Changes: By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Finland’s economy strengthened—wages rose, living standards improved, and emigration to Sweden slowed as gaps narrowed. Net immigration finally exceeded emigration starting in the early 1980s, but early inflows (1981–1989) were dominated by returning Finns (70% of total immigration), with non-EU migrants like Sikhs forming a tiny fraction. Significant non-Western immigration, including from Asia, only picked up in the late 1980s and 1990s amid EU integration and labor shortages in certain sectors.

- Contrast with Other Nordics: Sweden, Norway, and Denmark attracted South Asian labor migrants earlier due to post-war guest worker programs, colonial ties (e.g., British influence drawing Sikhs to the UK, then onward), and stronger economic booms in the 1960s–1970s. These countries built large Punjabi networks (e.g., ~5,000 Sikhs in Norway, ~4,000 each in Sweden and Denmark by the 1990s), creating “pull factors” like family reunification and job chains that Finland lacked until later.

Finland’s geographic isolation, harsh climate, and linguistically challenging Finnish language further deterred early migrants, making it less competitive than more accessible Western European hubs. migrationpolicy.org , journal-njmr.org

Sikh-Specific Factors: Labor Opportunities and Network Effects

Sikh migration from Punjab has historically been driven by economic aspirations, family ties, and chain migration rather than refugee flows or poverty alone. In Finland:

- Delayed Labor Pull: Unlike the UK’s textile mills or Canada’s farms in the mid-20th century, Finland offered few entry points for unskilled Punjabi labor until the 1980s. The first Sikhs (e.g., Sudarshan Singh Gill in 1985) often arrived via marriage or exploratory work visas, entering the burgeoning restaurant and hospitality sector amid Finland’s economic liberalization. By the 1990s, high unemployment among foreigners (peaking at 50%) paradoxically funneled Sikhs into niche roles like bar and pub ownership, where alcohol sales provided stable income and entrepreneurial paths—motivations tied to family aspirations rather than desperation.

- Routes via Neighboring Networks: Many early Finnish Sikhs migrated indirectly from Punjab through Sweden, where a large Punjabi diaspora (established in the 1960s) offered transit and connections. Sweden’s proximity and shared Nordic labor markets facilitated “secondary migration” once Finland’s borders opened more in the 1980s. This chain effect amplified growth in the 1990s, but the small scale reflects Finland’s late entry into global migration circuits.

- Diversification Pressures: By the 1980s, tightening borders in “prestige” destinations like the UK, US, and Canada pushed Sikhs toward “secondary” European sites like Finland, often for business regularization or family reasons.

- A secondary flows from the UK (post-1971 immigration curbs). Punjab’s 1984 anti-Sikh riots added a poignant asylum layer, but economics—better wages in eateries—dominated.

Ethnographer Laura Hirvi notes ~20-30% of early Finnish Sikhs were UK reroutes, arriving as young men in their 20s for better stability amid UK’s rising racial tensions.

In summary, the late start stemmed from Finland’s prolonged emigration phase and delayed economic attractiveness, compounded by Sikhs’ reliance on established networks elsewhere in Europe. This resulted in a modest, family-oriented community focused on service industries, with gurdwaras (e.g., in Helsinki since the 1990s) now anchoring cultural transmission. For deeper reading, see works by ethnographer Laura Hirvi on Sikh integration in Finland. api.pageplace.de , 375humanistia.helsinki.fi

Strong Punjabi/Sikh Presence in the Restaurant Sector

Sikhs in Finland excel in hospitality, helming eateries with Punjabi-Finnish fusions—like Mahaan Singh’s curry-salmon spots—yet most pivot to local pizzas, tapping untapped “Indian cuisine in Finland” potential.

The Sikh/Punjabi community has a disproportionately high and very visible presence in the Finnish restaurant sector, particularly in the independent pizza/kebab and Indian cuisine segments.

This ownership is a well-integrated part of Finland’s small business landscape and culinary culture.

Sikhs run an estimated 20% of Indian restaurants in Helsinki. While many eateries adapt to Finnish tastes, a few Sikh-owned ones proudly serve authentic Punjabi cuisine alongside more familiar options like pizza.

It is a widely recognized and visible fact in Finland that a significant number of restaurants, especially pizzerias and casual dining establishments, are owned by people of Punjabi origin, a large proportion of whom are Sikh.

Historical Context: This trend began in the 1980s and 1990s. Early immigrants from the Punjab region of India (both from India and, later, via other European countries) often entered the food service industry. They frequently purchased existing pizza/kebab restaurants, seeing it as a viable path to entrepreneurship.

A Common Phenomenon: It became so common that in Finnish casual parlance, “intialaispizza” (Indian pizza) or the phrase “pizzerian pitäjä” (pizzeria owner) became stereotypically associated with people of Indian/Punjabi background. Many of these restaurants serve a hybrid menu of pizzas, kebabs, burgers, and often some Indian dishes like chicken tikka masala.

Beyond Pizzerias: The community’s presence has since expanded to include:

Authentic Indian/Nepalese restaurants: Many of the highly-rated Indian restaurants in Helsinki and other cities are Sikh/Punjabi-owned.

Fine-dining establishments: Some entrepreneurs have moved into more upscale dining.

Food trucks and catering.

Kesh Retention Among Sikhs in Finland: Low

- Overview of Retention: In Finland’s ~600-700 Sikh community, kesh (uncut hair) retention is exceptionally low, with the vast majority of male Sikhs cutting their hair—a stark contrast to more visible practices in larger diasporas like California’s Yuba City.

- Percentage Estimate: No precise surveys exist, but ethnographer Laura Hirvi’s 2014 fieldwork estimates that “except for a few, the majority of male Sikhs have cut their hair,” implying 85-95% do not retain full kesh; only ~5 men (all immigrants) wear turbans daily, and amritdhari (initiated, kesh-mandatory) Sikhs number fewer than 5-10.

- Reason 1: Social Scrutiny and Racism: Finland’s homogeneous society (~8% foreign-born) amplifies curiosity and teasing; Sikhs report harassment (e.g., constant questions on trains: “What is this?”), leading many to cut hair to avoid standing out and blend in.

- Reason 2: Practical Convenience: Daily turban-tying is time-intensive in a fast-paced Nordic life; respondents cite “lack of time” and maintenance hassles, especially for young professionals in Helsinki’s service sector.

- Reason 3: Historical Trauma and Flight: Post-1984 anti-Sikh violence, some cut hair to evade persecution during migration (e.g., one informant: “I untied my turban, cut my hair and beard” to hide from authorities labeling turbaned Sikhs as “terrorists”).

- Reason 4: Generational and Peer Pressure: Second-generation Sikhs face school bullying or desire to “fit in” with Finnish peers; many trim hair in youth, with re-adoption rare without strong family/gurdwara reinforcement.

- Reason 5: Military and Workplace Norms: Finland’s army mandates haircuts for all recruits, barring turbaned Sikhs; similar uniform policies (e.g., 2014 bus driver case) push assimilation over religious expression.

- Cultural Adaptation in Isolation: Unlike California’s robust networks (where ~70% of young Sikhs retain kesh per U.S. surveys), Finland’s small, recent community (~1980s arrivals) fosters “ephemeral” practices—situational turban use for events, not daily life.

- Gender Dynamics: Sikh women often cover hair modestly (e.g., chunni at gurdwara) but face less pressure; retention ties to family izzat (honor), though overall, low male visibility reduces communal reinforcement.

- Implications: This pragmatic shift aids integration but sparks internal debate; retainers view kesh as core identity (“choose religion over money”), highlighting Sikhs’ global negotiation of faith in remote settings. library.oapen.org

Sikh Gurdwaras in Finland: History and Significance

The Sikh community formalized its religious structure in 1998 with the registration of Sarb Sangat as Finland’s official Sikh society, marking a pivotal step toward institutionalization. This laid the groundwork for dedicated gurdwaras, which serve not just as places of worship but as vital hubs for identity negotiation, langar (communal meals), and transmitting Punjabi heritage to second-generation children—essential in a diaspora isolated from larger Sikh networks. Today, Finland hosts two primary gurdwaras, reflecting the community’s modest scale and adaptive spirit.

1. Gurdwara Sarb Sangat Sahib (Helsinki)

- Location: Hämeentie 21, 00500 Helsinki (near Sörnäinen Metro Station).

- History: Established as the community’s cornerstone in 2006, this gurdwara emerged from informal home-based prayers in the 1980s–1990s, funded largely by congregants like entrepreneur Marinder Singh. Dedicated to Guru Gobind Singh Ji, it embodies resilience in a modest urban brick building, hosting weekly divans, Vaisakhi processions, and kirtan sessions. Early challenges included space constraints for the growing ~500 members (as of 2010), prompting plans for a purpose-built facility.

- Significance: As per ethnographer Laura Hirvi’s research, it functions as a “cosmos of significance,” blending religious rituals like prasad distribution with social integration, helping Sikhs navigate Finland’s welfare-state ethos while preserving traditions. Contact: +358 40 0701727; [email protected].

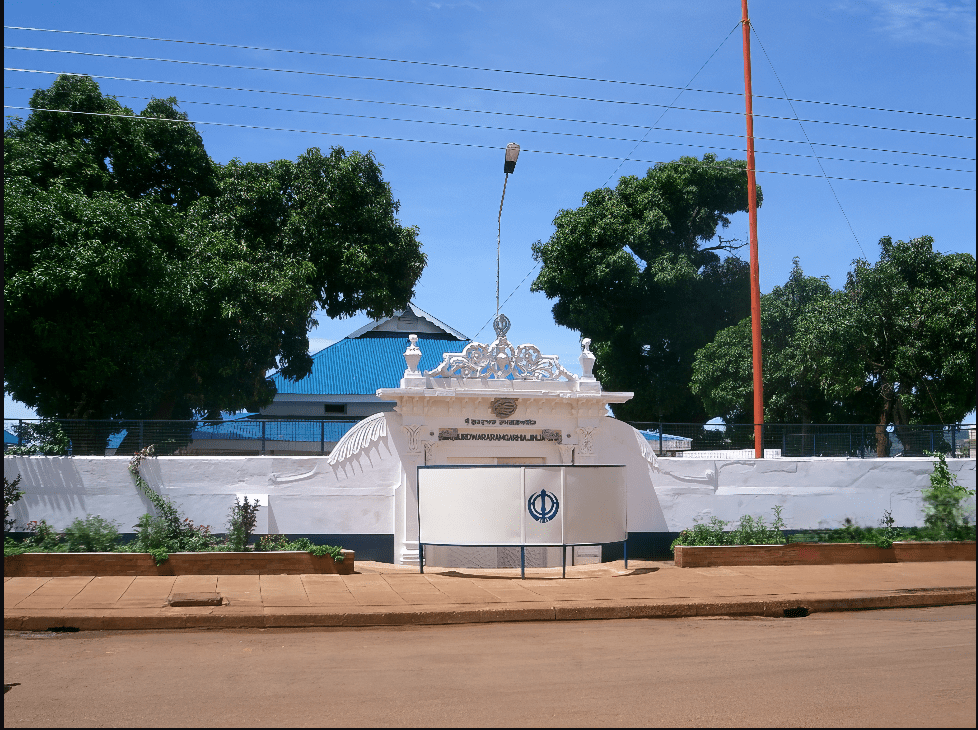

2. Gurudwara Vantaa (Vantaa)

- Location: Siriuksenpolku 1, 01450 Vantaa (Helsinki suburb).

- History: Opened in the early 2010s as an extension of the Helsinki community, it responded to suburban family growth post-2000s EU integration and secondary migration waves. Evolving from rented halls, it became a full-fledged gurdwara by 2012–2013, coinciding with heightened visibility from local events like the 2013–2014 turban rights case involving Vantaa bus driver Sudarshan Singh Gill. Limited documentation exists, but it mirrors the Helsinki model’s community-driven funding.

- Significance: Catering to commuter families, it emphasizes youth programs like Punjabi classes and Gurpurab celebrations, fostering intergenerational ties in a diverse suburb. It’s a welcoming space for all faiths, underscoring Sikh principles of equality.

These gurdwaras—amid Finland’s ~16,000 Indian-origin residents—highlight the diaspora’s quiet flourishing, with occasional informal prayer spots in cities like Tampere. Hirvi’s seminal work underscores their role in “contextual identity negotiation,” where Sikhs balance assimilation (e.g., many trim kesh for practicality) with core practices like seva. journal-njmr.org

Finland has been the modification of the Ardas (prayer), replacing “Bhagauti” with “Akal Purakh” and emphasizing the “Panth” (community) alongside the Guru Granth Sahib. This change, initiated locally, even prompted an inquiry committee from the SGPC in Punjab, showcasing the dynamic interplay between diaspora practices and traditional institutions. Community members discuss the “Finnish Ardas,” express concern, and report that Jathedar (Avtar Singh) Makkar of the Akal Takht had formed an inquiry committee consisting of members from the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) and the Dharam Parchar Committee to look into the matter. sikhphilosophy.net

Conclusion: A Flourishing Late Bloom

From the first arrivals in the 1980s to the legal victory for turban rights, Sikhs in Finland have carved a distinct space. They are a “late bloomer” diaspora—small in number but resilient. They have built institutions, fought for religious freedom, and contribute richly to Finland’s multicultural tapestry. Their journey from the fields of Punjab to the forests of Finland is a testament to the enduring and adaptable spirit of the Sikh faith.

This blog is based on historical accounts, scholarly research, and community reports. For the complete article with images and direct sources, visit globalsikhiwiki.com