Prabhjot Singh — Canadian Sikh Lawyer Who Challenged the Mandatory Oath

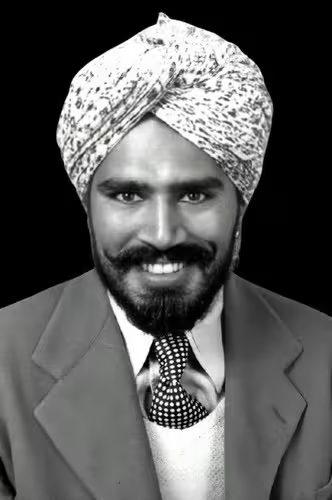

Who Is Prabhjot Singh?

Prabhjot Singh (full name Prabhjot Singh Wirring) is a Canadian lawyer of Sikh heritage. He was born and raised in Canada, though his family’s origins trace back to a small village in Punjab, India. Prabhjot Singh Wirring’s family traces its roots to Waring village (also spelled Warring) in the Sri Muktsar Sahib district of Punjab, India.

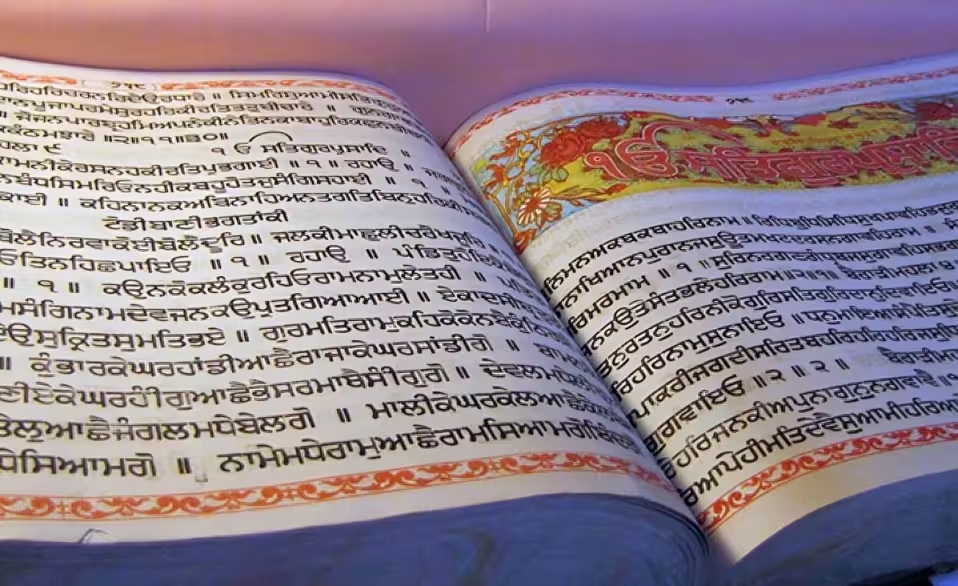

Singh is an Amritdhari Sikh, meaning he has taken formal Sikh initiation and follows the traditional religious code, which includes making a singular spiritual commitment to Akal Purakh (God) .

Akal Purakh-“Timeless Being” or “Eternal Person,” referring to the omnipresent, immortal Divine Reality beyond time and death, often used interchangeably with Waheguru, Karta Purakh (Creator)

The Legal Challenge: Why He Refused the Oath

When Singh applied for admission to the Alberta Bar (the legal profession in Alberta), he was required — under provincial regulations — to swear an Oath of Allegiance to the Monarch (King Charles III) as a condition for becoming a lawyer. The Times of India

However, Singh refused to take that oath for deeply held religious reasons:

As an Amritdhari Sikh, he believes he can give allegiance only to Akal Purakh (the Divine), and placing any human sovereign—even a constitutional monarch—above that was incompatible with his faith. The Times of India

He argued that being forced to swear allegiance to the King violated his freedom of religion under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms because it forced him to choose between his faith and practising his profession. CityNews Calgary

“I Cannot Place Anyone Above My Guru”

Prabhjot Singh’s refusal was simple, honest, and deeply rooted in Sikh philosophy.

As an Amritdhari Sikh, he had already taken an oath — not to a state, not to a crown, but to the Divine and to the principles laid down by the Sikh Gurus.

To swear allegiance to a monarch, even a constitutional one, felt like a violation of that spiritual commitment.

He did not argue politics.

He did not attack the monarchy.

He did not seek attention.He asked a single question:

Why must my faith be the price of my career?

Judicial Journey & Landmark Ruling

Singh first filed his legal challenge in June 2022 against the requirement in Alberta. A lower court initially dismissed the case, but he appealed. The case eventually reached the Alberta Court of Appeal. archive.vn

On 16 December 2025, a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeal unanimously ruled that the mandatory Oath of Allegiance to the monarch was unconstitutional because it infringed on the right to freedom of conscience and religion. The court held that forcing Singh — or anyone else — to swear allegiance to the monarch as a precondition for practicing law was too great a burden on those with sincere religious convictions. The Times of India

The court also stated that Alberta had options, including:

Making the oath optional,

Removing the oath altogether, or

Amending it to remove mandatory allegiance to the Crown. archive.vn

This ruling essentially ended the compulsory requirement in Alberta for lawyers to swear allegiance to the monarch to be admitted to the bar — a significant shift in tradition and policy in Canada. The Times of India

Canada Court vs Lawyer Prabhjot Singh

1. Singh’s Personal Statement

Singh himself clearly articulated why he could not take the oath:

“I am a Sikh of Guru Gobind Singh. I cannot consider anyone greater than my Guru.”

This statement was central to his legal argument, showing that his religious conviction prevented him from pledging allegiance to any human sovereign because he had already made an absolute oath of devotion to the Divine (Akal Purakh). India Today

2. Court’s Interpretation of the Conflict

The Alberta Court of Appeal explained the conflict between the oath requirement and Singh’s religious freedom:

“Wirring had sworn an allegiance to Akal Purakh, or the Creator in the Sikh faith, and couldn’t make an allegiance or devotion to any other figure or entity, including in the Oath of Allegiance to become a lawyer.”

This line in the ruling shows the court recognised that the oath requirement forced Singh into a choice between his faith and his profession, which violated his fundamental rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. lethbridgeherald.com

3. Court’s Constitutional Finding

The court also emphasised the broader implications of maintaining the oath:

“This case shows the real possibility that candidates with religious objections to the Oath of Allegiance may choose not to become members of the Alberta bar diminishing the bar’s representativeness.”

This quote reflects the court’s concern that mandatory allegiance to the monarch could deter qualified applicants from diverse backgrounds, thereby harming inclusivity in the legal profession. lethbridgeherald.com

4. Wider Context from Charter Law Arguments

Earlier legal materials (from the BC Civil Liberties Association intervention) framed the case as not only about individual rights but also about collective religious practice and multiculturalism, arguing that forcing such an oath could unfairly impede participation in society for religious communities. BC Civil Liberties Association

What the Case Means

Religious freedom affirmed: The case affirmed that professional requirements cannot force individuals to violate their religious beliefs. CityNews Calgary

Legal precedent: The decision opens the door for other religious minorities and individuals with conscience objections to contest similar requirements. The Times of India

Modern pluralism: It reflects Canada’s commitment to pluralistic values and the flexibility of its legal system in accommodating diversity. CityNews Calgary

Public and Legal Responses

Civil liberties groups welcomed the ruling, viewing it as a victory for individual rights and freedom of religion. New India Abroad

Supporters pointed out that the case not only benefits religious minorities but could also help Indigenous peoples and others who have moral or ethical objections to the oath. canadianlawyermag.com

Critics argued that the Crown and the monarchical system are foundational to Canada’s constitutional structure, and some saw the decision as weakening traditional symbols of state. Yahoo News Canada

Why This Case Matters to Sikh History

From a Sikh historical perspective, Prabhjot Singh’s stand fits into a long tradition of non-violent resistance grounded in conscience.

Sikh history is replete with moments where individuals chose dharam (righteous duty) over authority:

Guru Tegh Bahadur’s martyrdom for religious freedom

Sikh resistance to forced religious oaths during Mughal and colonial rule

Diasporic Sikh struggles for religious accommodation in Western institutions

Singh’s case represents a modern, constitutional continuation of this tradition — not through martyrdom, but through legal reasoning and moral clarity.

Global Reactions and Wider Implications

Prabhjot Singh’s victory is not merely a legal technicality. It is a philosophical moment.

It asks uncomfortable but necessary questions:

Can a state demand symbolic loyalty that contradicts faith?

Is tradition more important than inclusion?

Does diversity mean tolerance — or genuine accommodation?

For Sikhs worldwide, the case resonated deeply. It echoed the Sikh historical tradition of standing firm against authority when conscience is at stake — from Guru Tegh Bahadur to modern diasporic struggles.

For minorities everywhere, it sent a quiet but powerful message:

Your faith does not make you less worthy of citizenship.

The ruling was welcomed by:

Civil liberties organizations, who saw it as a victory for freedom of conscience

Sikh communities worldwide, who viewed it as recognition of Sikh religious principles

Legal scholars, who noted its implications for other professions and minority rights

The decision may also influence:

Indigenous objections to Crown-based oaths

Other religious minorities facing conscience-based conflicts

Future debates on the role of monarchy in multicultural democracies