Superstitions in Sikh Society: A Cultural Exploration in Global Sikh Communities

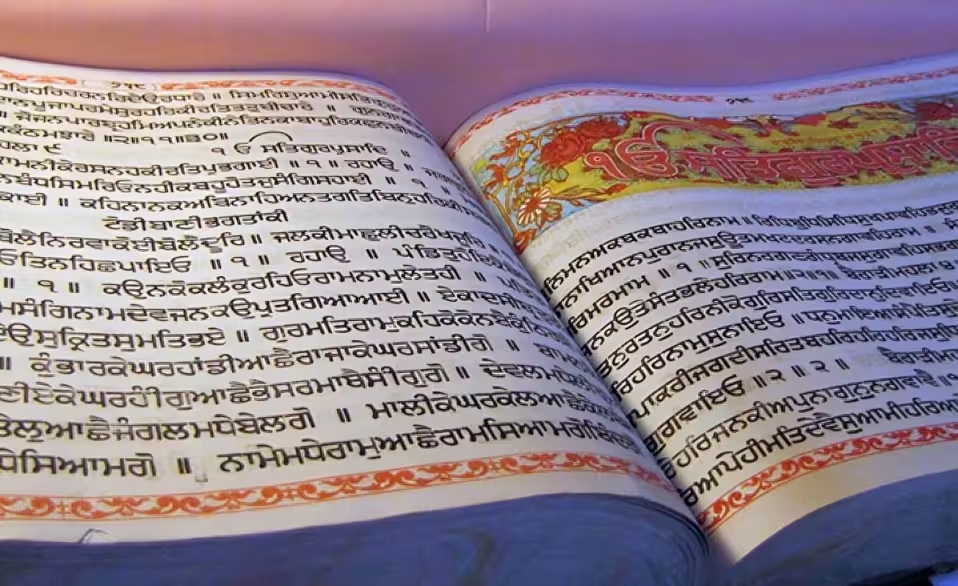

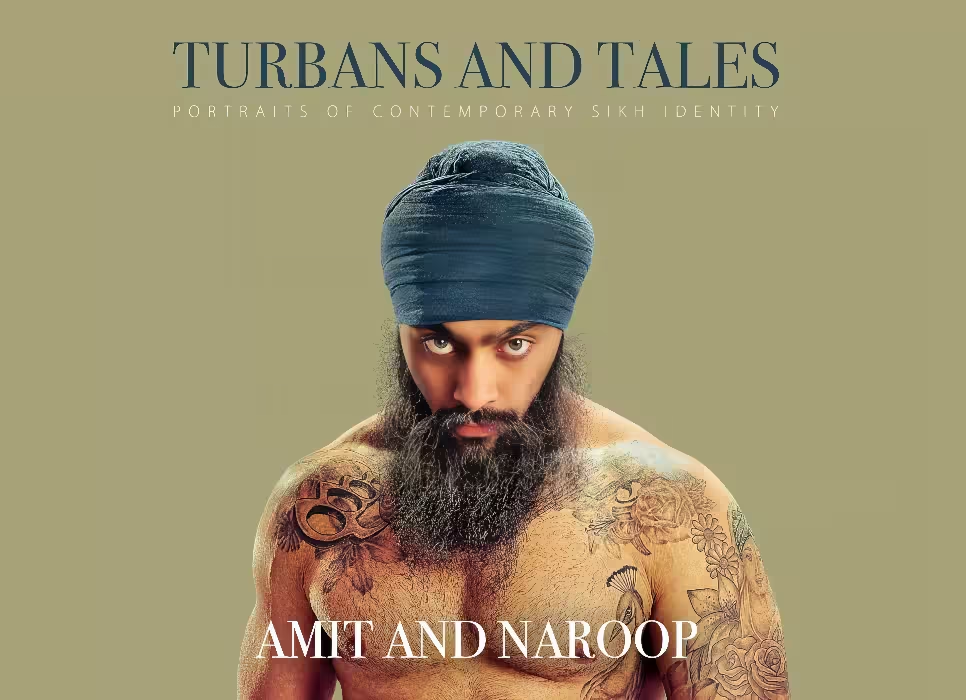

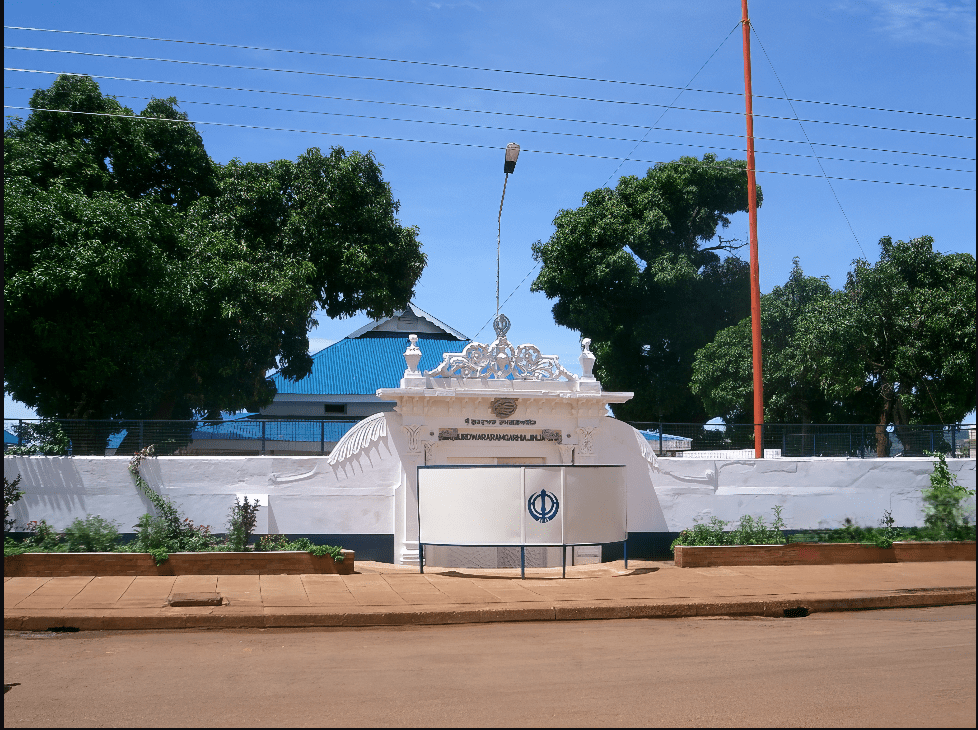

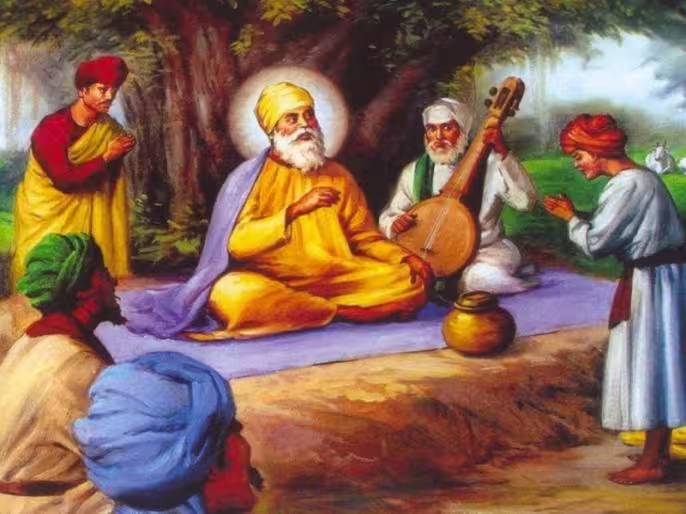

As we trace the global migration of Sikhs on globalsikhiwiki.com—from Punjab’s heartlands to settlements in Canada, the UK, Australia, and beyond—Guru Nanak Dev Ji’s teachings remain a guiding light. Born in 1469 in Talwandi (now Nankana Sahib, Pakistan), the founder of Sikhism challenged the ritualistic and superstitious practices of his time, promoting rational devotion, equality, and ethical living. These anti-superstition stories not only reformed society in 15th-century Punjab but also equipped Sikhs with a resilient mindset for migrations. Amid challenges like discrimination in new countries or cultural adaptations, Sikhs drew from Guru Nanak’s emphasis on inner truth over blind beliefs, fostering achievements in fields like agriculture, business, and activism while building Gurdwaras as centers of rational community life. Let’s explore key stories from his life, drawn from traditional Janamsakhis (biographies) and the Guru Granth Sahib.

The Rejection of the Sacred Thread (Janeu) Ceremony

One of the earliest demonstrations of Guru Nanak’s critique of superstition occurred around 1478, when he was about nine years old. In Hindu tradition, the Janeu ceremony involves tying a sacred thread around a boy’s body as a rite of passage, symbolizing spiritual purity, caste status, and protection from evil. Families believed this thread warded off misfortune and ensured divine favor, a superstition rooted in Brahminical hierarchy.

Guru Nanak refused to participate, questioning the priest: “If this thread brings purity, why not make one for the soul that doesn’t break?” He argued that true purity comes from compassion, contentment, and truth—not a fragile cotton string. This act rejected caste-based superstitions and empty rituals, emphasizing inner devotion (Naam) over external symbols. As recorded in Janamsakhis, his family was astonished, but this moment sparked his lifelong mission against irrational practices. sikhnet.com

This teaching resonated during Sikh migrations. In countries like the United States, where early 20th-century Sikh laborers faced racial exclusion (e.g., the Asiatic Barred Zone Act of 1917), adherents avoided superstitious fears, focusing instead on hard work and community building. Famous Sikhs like Bhagat Singh Thind, who fought for citizenship in 1923, embodied this rational spirit, drawing from Guru Nanak’s rejection of divisive rituals to advocate equality. sikhiwiki.org

The Immersion in the Bein River: A Declaration Against Sectarian Rituals

Around 1499–1504, while working as a storekeeper in Sultanpur Lodhi under a local Muslim governor, Guru Nanak experienced a profound event that directly challenged ritualistic divisions. He would bathe daily in the Bein River for meditation. One morning, he immersed himself and disappeared for three days, presumed drowned by villagers gripped by superstitious fears of spirits or divine punishment.

Emerging unscathed, he proclaimed: “Na koi Hindu, na koi Musalman” (There is no Hindu, no Muslim)—a rejection of sectarian labels and the rituals that divided them, like Hindu pilgrimages or Islamic ablutions without inner sincerity. This story, central to Sikh lore, underscores that true spirituality transcends superstitious boundaries, focusing on universal humanity and devotion to one God (Ik Onkar).

In global contexts, this message aided Sikhs in multicultural settlements. During the 1984 anti-Sikh violence in India, which spurred migrations to places like the UK, survivors rebuilt lives through Gurdwaras emphasizing unity over fear-based rituals. Achievements like those of Canadian Sikh politician Jagmeet Singh reflect this: rising above adversity with rational advocacy, free from superstitious hindrances. barusahib.org