Sikhs in UK : A Historical and Cultural Overview

🧭 Introduction

Sikhs in UK – The United Kingdom holds a special place in the Sikh diaspora’s journey. It is home to one of the largest Sikh communities outside India, with deep historical ties dating back to the British Raj and World Wars. From early military service to post-war migration, Sikhs have shaped the cultural, political, and economic fabric of the UK. Today, cities like London, Birmingham, and Leicester are vibrant centers of Sikh life, with gurdwaras, schools, and MPs representing Sikh voices—reflecting both their integration and the preservation of their distinct identity.

Today, with over 5,35,000 Sikhs, the UK is home to one of the largest Sikh communities outside India.

Fourth largest religious group in England after Christians, Muslims and Hindus

Nanak Naam - UK-based non-profit charity

Satpal Singh is a UK-based educator and founder of the non-profit charity Nanak Naam.

The organisation focuses on sharing Sikh wisdom in a modern, accessible way.

It offers guided meditations, talks, and courses that blend spirituality with everyday life.

Nanak Naam aims to make Guru Nanak’s message relevant for people of all backgrounds.

Through online platforms and global outreach, it helps individuals find inner peace and purpose.

Satpal Singh, also known as Bhai Satpal Singh, left a career in technology to dedicate his life to spiritual education.

He delivers talks and workshops around the world, often translating complex Sikh teachings into simple, relatable concepts.

Nanak Naam provides both in-person and online resources, including podcasts, YouTube videos, and structured learning programmes.

The charity is committed to remaining free of ritualism and sectarian divides, keeping its focus on the universal truths in Sikh philosophy.

Its mission is to help people apply meditation, mindfulness, and Gurbani wisdom to live happier, more fulfilled lives.

Sikh in UK: Unique Stories and Historical Facts of Migration

The Sikh community’s presence in the United Kingdom is a rich tapestry of resilience, adaptation, and cultural preservation, shaped by waves of migration from the mid-19th century to the present. Beyond the well-documented milestones, such as Maharaja Duleep Singh’s arrival in 1854 and the establishment of the first Gurdwara in 1911, this account delves into unique, lesser-known stories of Sikh migration, drawn from books that highlight personal struggles, triumphs, and community-building efforts. These narratives reflect the Sikh diaspora’s contributions to British society, their challenges with prejudice, and their unwavering commitment to maintaining their religious and cultural identity.

Early Sikh Migration: The Untold Struggles of the Pioneers

While Maharaja Duleep Singh’s (nicknamed the “Black Prince of Perthshire”) arrival in 1854 marked the first recorded Sikh presence in Britain, the early 20th century saw a gradual influx of Sikh men, primarily from Punjab’s Jullundur Doab region, seeking economic opportunities. These pioneers faced significant challenges, including racial prejudice and economic hardship, which often forced them to make difficult choices about their religious identity.

Living the life of a Scottish aristocrat-Maharaja Duleep Singh

During his teenage and early twenties, he lived in various locations in Scotland in Perthshire, including Castle Menzies and houses in Auchlyne and Aberfeldy. He was known at that time for his love of the classic Highland lifestyle – shooting parties and dressing in Highland costume.

Duleep Singh died at the age of 56 and his son Victor Duleep Singh may have inherited some of his jewellery. He sold the jewellery because he was in debt. Dasvandh Network

The famous diamond currently set in the crown of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother – the Koh-i-noor – was one of the items that is claimed to have been gifted by Duleep Singh to Queen Victoria – although this was done when the Maharaja was a minor. Soctsman

The Pedlars of the 1930s: A Tale of Resilience

In the 1930s, many Sikh immigrants worked as pedlars, selling goods door-to-door in industrial towns like Birmingham, Leeds, and London’s Southall. One compelling story comes from Sikhs in Britain: The Making of a Community by Gurharpal Singh and Darshan Singh Tatla. The book recounts the life of a Sikh pedlar named Gurdial Singh, who arrived in Birmingham in 1932. Unable to secure factory work due to discrimination, Gurdial sold clothes and household goods from a suitcase, walking miles daily to support his family back in Punjab. To blend in and avoid harassment, he reluctantly trimmed his beard and removed his turban, a decision that caused him deep personal conflict. His story reflects the broader struggle of early Sikh immigrants who balanced economic survival with religious identity. Gurdial later became a founding member of a local Gurdwara, using his earnings to support community initiatives, illustrating the resilience and communal spirit of early Sikhs

Gurharpal Singh & Darshan Singh Tatla — Sikhs in Britain: The Making of a Community

A comprehensive sociological history including personal letters and oral histories of early migrants who hid their turbans or cut beards to enter foundry jobs in Birmingham or Bradford in the 1930s–40s .

The book includes less‑known accounts: like Punjabi soldiers awarded British Army medals who later became community organizers in Wolverhampton or founded informal Punjabi mutual aid societies.

Knut A. Jacobsen (ed.) — Sikhs Across Borders

Contains cases of early Sikh pedagogue‑missionaries and soldiers in European cities before World War II, forming small phosphor‑lit gurdwara gatherings in Liverpool, Cardiff, and Glasgow, often under the radar of official records .

Post-War Migration: The Chain Migration Phenomenon

The post-World War II period marked a significant wave of Sikh migration, driven by Britain’s need for labor to rebuild its economy. This era saw the phenomenon of “chain migration,” where early settlers sponsored relatives from Punjab, leading to the growth of Sikh communities in places like Southall, Smethwick, and Wolverhampton.

The “Little Punjabs” of Britain

In book ” Sikhs in Britain”: The Making of a Community, the authors describe how Sikh migrants from specific villages in Punjab recreated their communities in the UK, forming what they called “Little Punjabs.” One such story is of the village of Bilga in Jullundur, where nearly every household had a member migrate to the UK in the 1950s and 1960s. By 1970, Bilga’s diaspora had established a strong presence in Southall, with families pooling resources to buy homes and establish the first Gurdwara in the area. This chain migration not only preserved cultural ties but also led to the economic upliftment of entire villages back in Punjab, as remittances funded schools and infrastructure. The book highlights how these tight-knit communities maintained Sikh traditions, such as the langar (community kitchen), despite living in cramped, shared accommodations.

Sikh Women’s Contributions: Hidden Voices

While early Sikh migration was male-dominated, women played a crucial role in shaping the community, often overlooked in mainstream narratives. The Lost Heer: “Women in Colonial Punjab” by Harleen Singh provides a unique perspective on Sikh women who migrated to the UK in the 1960s and 1970s.

The Story of Bibi Jaswant Kaur

One poignant story is that of Bibi Jaswant Kaur, who arrived in Leicester in 1965 to join her husband, a factory worker. As described in Singh’s book, Jaswant faced isolation in a foreign land, unable to speak English and confined to domestic life. Determined to preserve Sikh values, she organized weekly kirtan (devotional singing) sessions in her home, inviting other Sikh women to join. These gatherings became a lifeline for the women, fostering a sense of community and cultural continuity. Jaswant’s efforts led to the establishment of a women’s group that advocated for Punjabi language classes and childcare support, empowering Sikh women to navigate British society while maintaining their identity. Her story underscores the vital, yet often invisible, role of women in building the Sikh diaspora.

Rani Nur‑un‑Nissa of Ludhiana

Rani Nur‑un‑Nissa, the widow chieftain of Raikot near Ludhiana, assumed political leadership in the early 19th century after her husband’s death. She governed her domain for sixteen years amid patriarchal resistance and threats from rival regional powers, including the Sikh leader Sahib Singh Bedi. To protect her sons and territory, she engaged directly in politics—a role seldom recorded for Punjabi women of the era. The Free Library

In a bold move around 1799, Nur‑un‑Nissa negotiated with George Thomas, an Irish adventurer ruling parts of Punjab, offering a pension of one lakh rupees in exchange for safe passage and protection for herself and her children. This was extraordinary: as a Punjabi woman, she openly bargained with a European power—an act of political agency seldom attributed to women in colonial-era Punjab. The Tribune

She successfully thwarted Sahib Singh Bedi’s attempt to seize her territory and secured British recognition and a pension—marking her out as a savvy and determined female ruler in a male-dominated political world .

The East African Sikh Exodus: A Unique Migration

A lesser-known wave of Sikh migration came from East Africa, particularly after Uganda’s expulsion of Asians in 1972 under Idi Amin. The Sikhs in Britain: 150 Years of Photographs by Peter Bance captures the stories of these “twice migrants” who brought a distinct cultural blend to the UK.

The Journey of Pritam Singh

Pritam Singh, a Sikh engineer from Nairobi, arrived in the UK in 1972 after being expelled from Uganda. As recounted in Bance’s book, Pritam had built a successful life in Kenya, where his family ran a construction business. Forced to leave with little more than a suitcase, he settled in London’s Ealing borough. Despite starting over, Pritam used his skills to establish a small engineering firm, employing other Sikh refugees. His story highlights the adaptability of East African Sikhs, who brought with them a unique blend of Punjabi and colonial influences, such as fluency in English and familiarity with British administrative systems, which helped them integrate more quickly than their Punjab-born counterparts.

The Bhogal Family: From Nairobi Refugees to British Pioneers

Born in Nairobi in 1953 into a Sikh family, Bhogal and his family were forced to leave Kenya in 1964 under the wave of Africanisation policies that restricted non-citizens. They arrived in the UK as refugees, settling in Dudley, West Midlands when he was about eleven years old.

With no local Sikh temple, young Inderjit began attending a Methodist church. He went on to pursue higher education at Manchester, followed by postgraduate studies at Oxford and Sheffield. His faith journey evolved and he eventually became a Christian minister.

In 2000, he made history as the first person from a minority ethnic background to be appointed President of the Methodist Conference in Britain and founded the City of Sanctuary UK — a network welcoming refugees across the country.

Peter Bance ( born Bhupinder Singh Bance, is a Sikh historian, author, art collector, antiquarian, and Maharaja Duleep Singh archivist ) has created a unique volume, “The Sikhs in Britain” with a pictorial history of the Diaspora Sikhs in UK. In author’s view, the Sikhs have added a little something to Britain. He recounts Guru Nanak Marg, Khalsa Avenue, Glassy Junction, Bhangra music and many more landmarks of Punjabi culture in London.

Piara Singh Kenth: The First Sikh Police Officer in London

Originally from Kenya, Kenth was a Sub‑Inspector in the Kenya Police Force before retiring around 1969. That same year, he moved to the UK to continue policing. The Justice Gap

He applied to the Metropolitan Police and in July 1969 became the UK’s first Sikh police officer, serving initially in Ealing during probation and then in Southall, where his language skills were crucial.

Despite facing prejudice, including being questioned by a sergeant and media mischaracterisation of his accent, Kenth performed successfully in CID cases and earned commendations from senior Crown Court judges.

Sikh Contributions to British Society: Beyond the Gurdwara

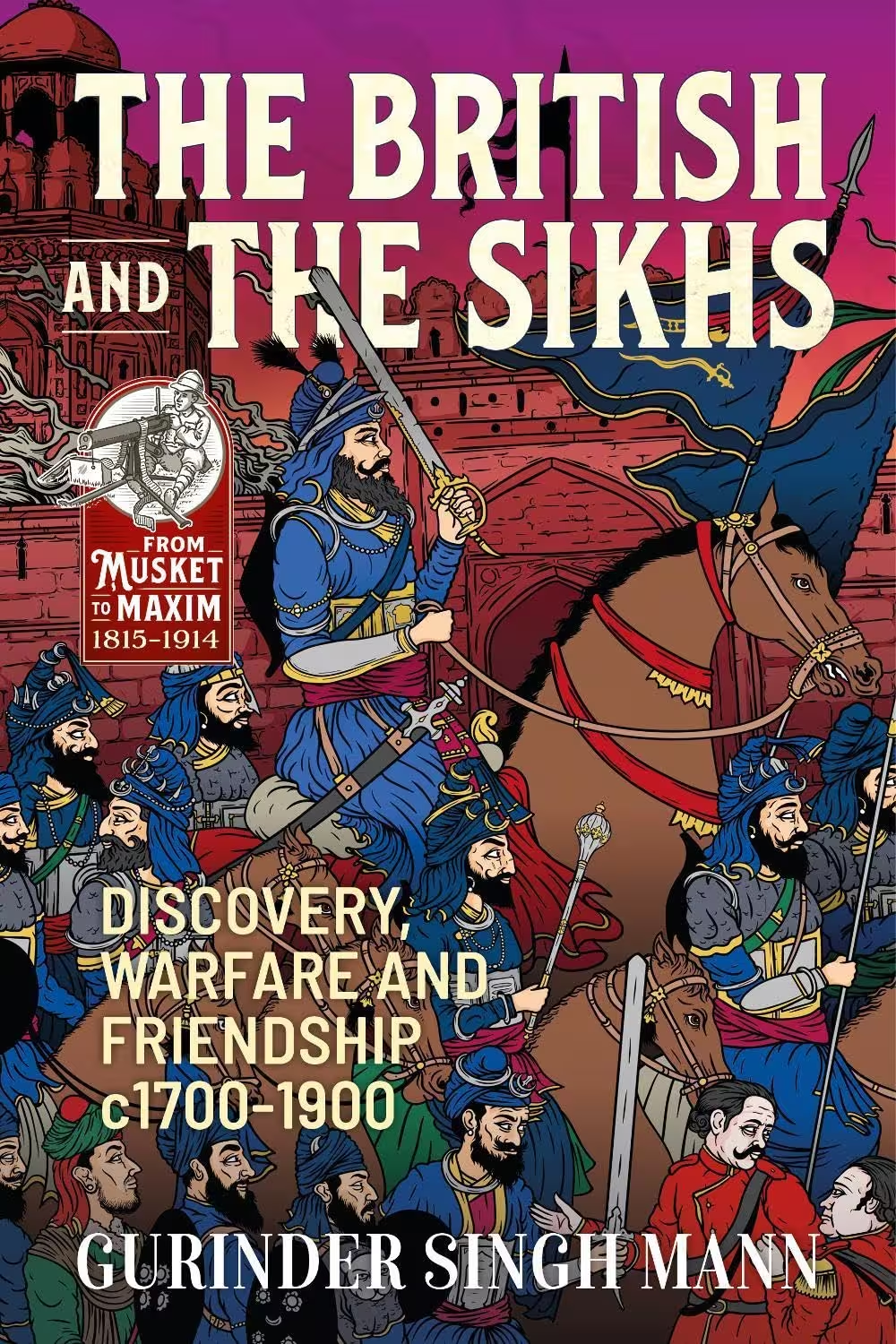

Sikhs have left an indelible mark on British society, from politics to public services, often overcoming significant barriers. The British and the Sikhs by Gurinder Singh Mann provides unique insights into Sikh contributions during the British Raj and beyond.

The First Sikh Policeman: Sundar Singh

One remarkable story is that of Sundar Singh, who became one of the first Sikh policemen in London in the 1950s. As detailed in Mann’s book, Sundar faced skepticism from colleagues who questioned whether his turban could fit under a police helmet. Undeterred, he worked with the Metropolitan Police to design a turban compatible with the uniform, setting a precedent for Sikh officers. Sundar’s persistence not only paved the way for future Sikh policemen but also challenged stereotypes, showcasing Sikh commitment to public service. His story is a testament to the community’s efforts to integrate while preserving their religious symbols.

Contemporary Sikh Identity: Navigating Multiculturalism

In recent decades, Sikhs in the UK have navigated the complexities of multiculturalism, balancing their heritage with British identity. Sikh View on Happiness: Guru Arjan’s Sukhmani by Nayar and Sandhu explores how Sikh philosophy has guided the community through modern challenges.

The 2016 Leamington Spa Protests

A unique contemporary story involves the 2016 protests at Gurdwara Sahib in Leamington Spa over interfaith Anand Karaj ceremonies. As noted in Sikh View on Happiness, the protests highlighted tensions within the Sikh community about preserving religious traditions in a multicultural society. A young Sikh couple, one of whom was non-Sikh, faced opposition from traditionalists who argued that Anand Karaj should be reserved for Sikhs. The couple, supported by moderate Sikhs, organized community dialogues to promote understanding, drawing on Guru Arjan’s teachings of compassion and unity. This story reflects the ongoing evolution of Sikh identity in the UK, where younger generations navigate tradition and modernity.

Conclusion

The Sikh presence in the UK is a story of courage, adaptation, and cultural preservation, woven through the lives of individuals like Gurdial Singh, Bibi Jaswant Kaur, Pritam Singh, and Sundar Singh. From the pedlars of the 1930s to the East African exiles of the 1970s and the modern debates over identity, Sikhs have built a vibrant community while contributing to Britain’s multicultural fabric. These stories, drawn from scholarly books, highlight the resilience and diversity of the Sikh diaspora, offering a deeper understanding of their historical and contemporary journey.

Racism in UK

In the UK, Sikhs faced considerable racism during the early 1980s, particularly as a visible minority due to their distinct religious and cultural identity, including the turban and the five articles of faith (the five K’s, such as kesh or unshorn hair). This period was marked by widespread anti-immigrant sentiment, especially against South Asians, who were often collectively targeted with derogatory terms like “Pakis” by racists. The early 1980s saw economic challenges and social tensions in the UK, including high unemployment and urban unrest (e.g., the 1981 Brixton and Toxteth riots), which fueled racial hostility. Sikhs, many of whom had migrated to the UK in significant numbers since the 1950s following the 1947 partition of India, were often compelled to compromise their religious identity to secure employment. For example, some were pressured to cut their hair and remove their turbans due to discriminatory workplace policies or societal prejudice, which was seen as a failure of UK policymakers to accommodate diversity. Sikh Missionary Society

Institutional racism

Institutional racism was also evident. Sikh lawyer Sukhvinder Thandi argued that state powers and policies tended to favor uniformity, effectively conspiring against diverse cultural identities like that of the Sikhs. This is exemplified by cases where Sikhs had to take legal action to secure basic religious rights, such as the right to wear a turban or carry a kirpan (a ceremonial dagger). These rights were often only grudgingly conceded by public and private sectors after court battles, reflecting resistance from policymakers and civil servants. For instance, the 1983 House of Lords ruling in Mandla v. Lee recognized Sikhs as an ethnic group under UK law, a significant victory, but it highlighted the ongoing struggle for recognition. Asia Samachar

"I am not a racist. I am against every form of racism and segregation, every form of discrimination. I believe in human beings, and that all human beings should be respected as such, regardless of their color."

Malcolm X Tweet

Specific incidents of Racism

Specific incidents from the period illustrate the racism Sikhs faced. In 1977, just before the early 1980s, three Sikh brothers (Mohinder, Balvinder, and Sukvinder Virk) were racially abused and attacked by White youths in East London while repairing their car, showing the physical and verbal hostility prevalent at the time. Additionally, the UK Sikh Survey 2016 noted that Sikhs who wore religious symbols, like the turban, were more likely to face abuse, a trend that was already evident in the 1970s and 1980s. This visibility made Sikhs particularly vulnerable, with some experiencing internalized racism or pressure to conform by abandoning their religious practices to “fit in.” The Guardian

Sikhs as "model minority"

While the Sikh community has since been recognized as a “model minority” for their integration and contributions to the UK (e.g., through military service, economic success, and legal advocacy), the early 1980s were a challenging time. The racism they faced was not a “natural” trait of any group but rather a product of societal ignorance, economic pressures, and institutional failures to embrace diversity. This mirrors the broader experience of minorities in Western countries during that era, including the US.

The Story of Mohinder Singh Saran: A Tailor from Punjab to Birmingham (1958)

- In 1958, Mohinder Singh Saran, a 22-year-old from Hoshiarpur district, Punjab, boarded a flight from Delhi to London Heathrow with a single suitcase and £3 in his pocket. Like many young Sikhs of the time, he was drawn by the promise of work and stability in post-war Britain, which was actively recruiting Commonwealth citizens for labor.

2. After arriving in London, he travelled by train to Birmingham, where his cousin had secured him a job at a textile mill. Within months, he switched to tailoring—his lifelong skill—and rented a tiny room in Smethwick, sharing it with four others

3. By 1962, Mohinder had saved enough to open his own tailoring shop on Soho Road, which became popular among both South Asian and British clients. He was known for sewing Western-style suits with a Punjabi touch and would often close the shop during Gurpurabs to attend the Soho Road Gurdwara, one of the earliest Sikh centers in the UK.

4. In 1970, he sponsored his wife and two children to join him under the UK’s family reunification scheme. He later became a founding member of the Guru Nanak Nishkam Sewak Jatha, helping build community cohesion and offering free tailoring lessons to newcomers.

5. By the time of his retirement in 1998, Mohinder Singh had mentored over 60 young Sikhs, many of whom started their own shops in the Midlands.

For the first time ever, Virgin Atlantic flew with both Captain Jaspal Singh and son First Officer Harinder Singh at the helm — a proud first for the airline and a powerful moment for the Sikh community across the globe.

Not just pilots. Panth da maan.

Not just a flight. A flight into history.

With turbans on and hearts full, they flew not just a plane, but the dreams of generations that never saw themselves in this seat.

Representation like this? It’s not just rare—it’s revolutionary.

Contributed by Pritpal Singh Mehta.